Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

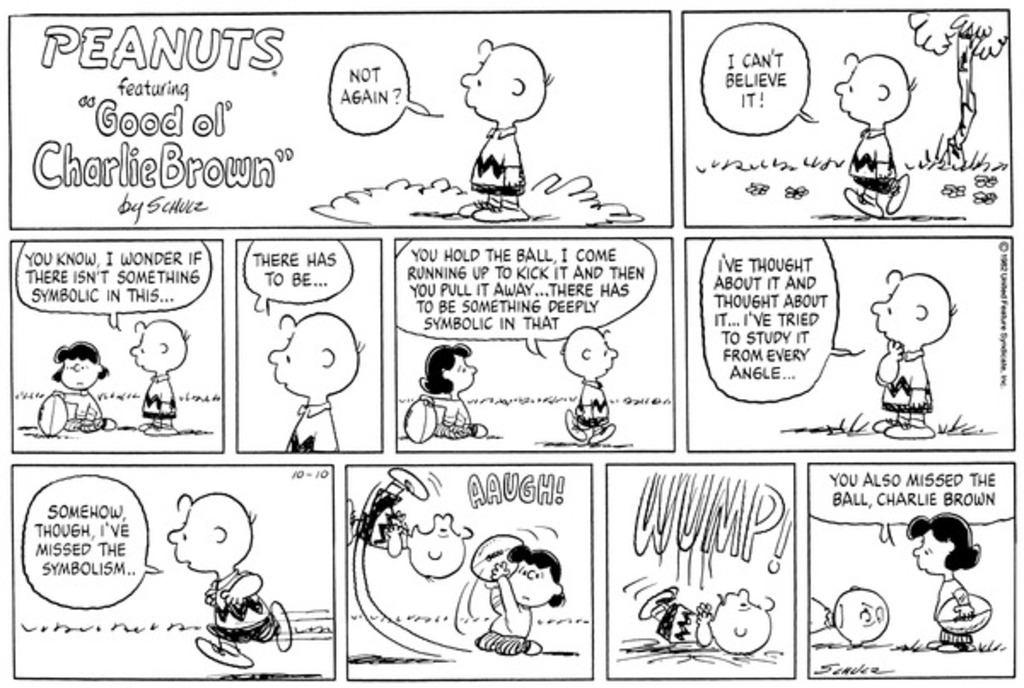

Schmid’s ‘Charlie Brown Phenomenon’

‘participants in joint action are usually focused on whatever it is they are jointly doing rather than on each other. Where joint action goes smoothly, the participants are not thinking about the others anymore than they are thinking about themselves’

Schmid (2013, p. 37)

‘cooperators normatively expect their partners to cooperate; they do not predict their cooperation’

Dominant View: ‘the representation of the participation of the others has a mind-to-world direction of fit.’

Alternative View: ‘the representation of the participation of the others has a world-to-mind direction of fit.’

Schmid (2013, p. 38)

Team reasoning

Schmid

Participants reason about what team-directed preferences require (so do not distinguish themselves from others).

‘individual agents of temporally extended actions “represent” their own future intentions and actions in the same way in which cooperators represent their partners’ intentions and actions.’

Schmid (2013, p. 49)

How do cooperators represent their partners’ actions?

‘this representation is neither (purely) cognitive nor (purely) normative, but rather a very peculiar combination of the two. ’

Compare representing your own actions:

‘An individual with a purely cognitive stance toward his own future self’s behavior and no normative expectation is a predictor of his behavior rather than an intender of his future action; similarly, an individual with a purely normative stance toward his own future behavior is a judge over [...] his future behavior rather than an agent.’

Schmid (2013, p. 50)

How can we turn these observations into a theory?

PS: Are we still talking about aggregate agents?