Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Why Not Take ‘Shared Intention’ Literally?

‘shared’ 1 : Ayesha and her best friend have the same haircut

-> the Simple View

‘shared’ 2 : Ayesha and her brother share a mother

-> plural subject account (Schmid, Helm)

e.g. our volume, yours and mine, is approx 130 litres.

cf. our intention, yours and mine, is that we paint the house.

‘shared’ 1 : Ayesha and her best friend share a name

-> the Simple View

‘shared’ 2 : Ayesha and her brother share a mother

-> plural subject account

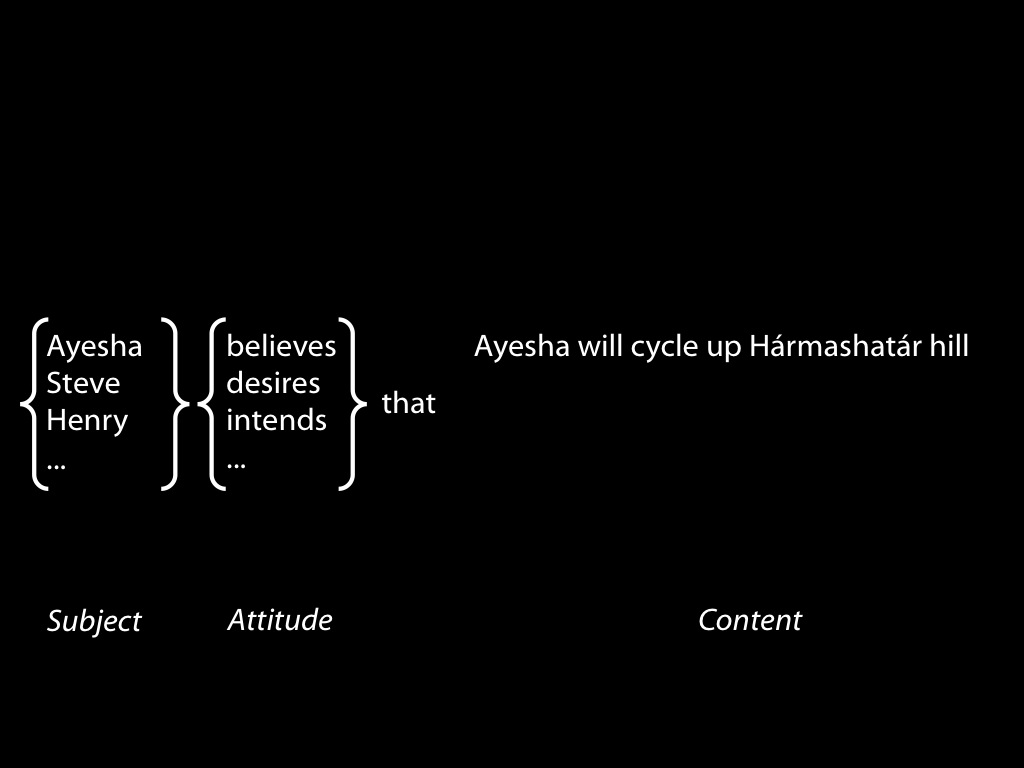

Can intentions have

plural subjects?

?

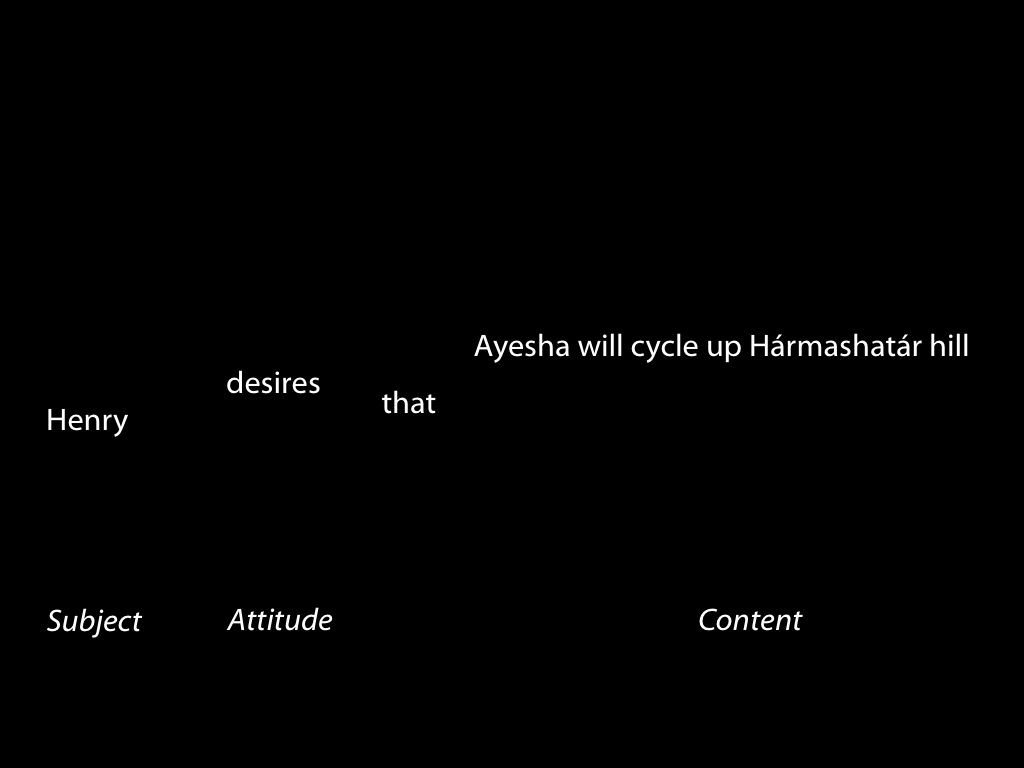

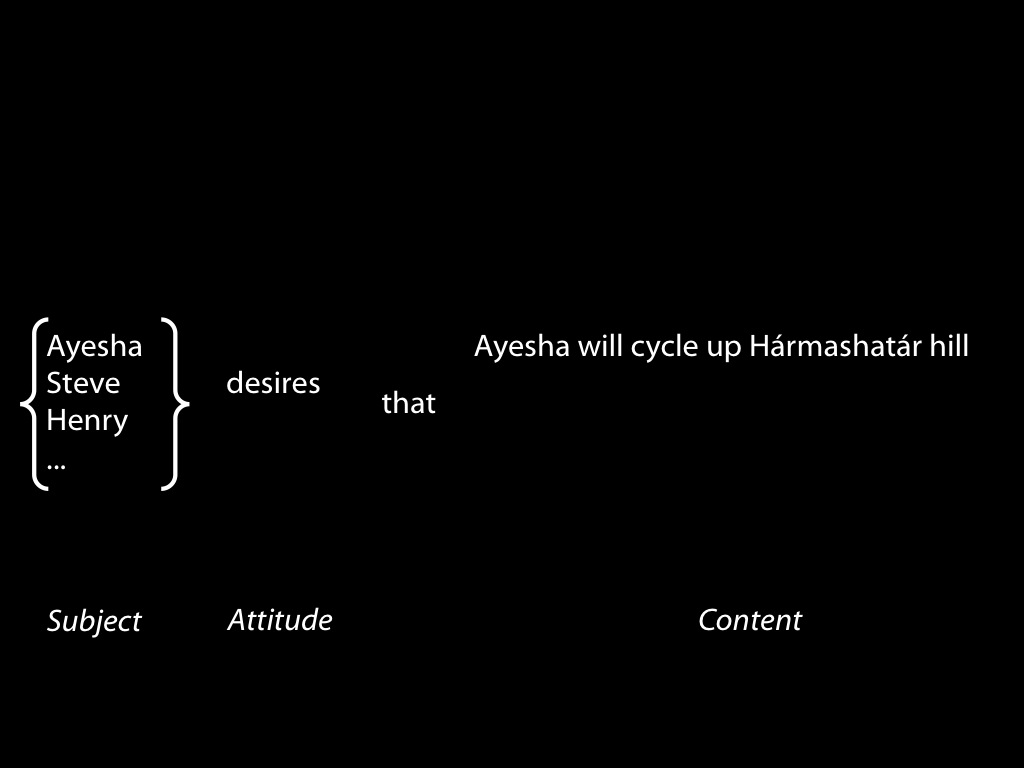

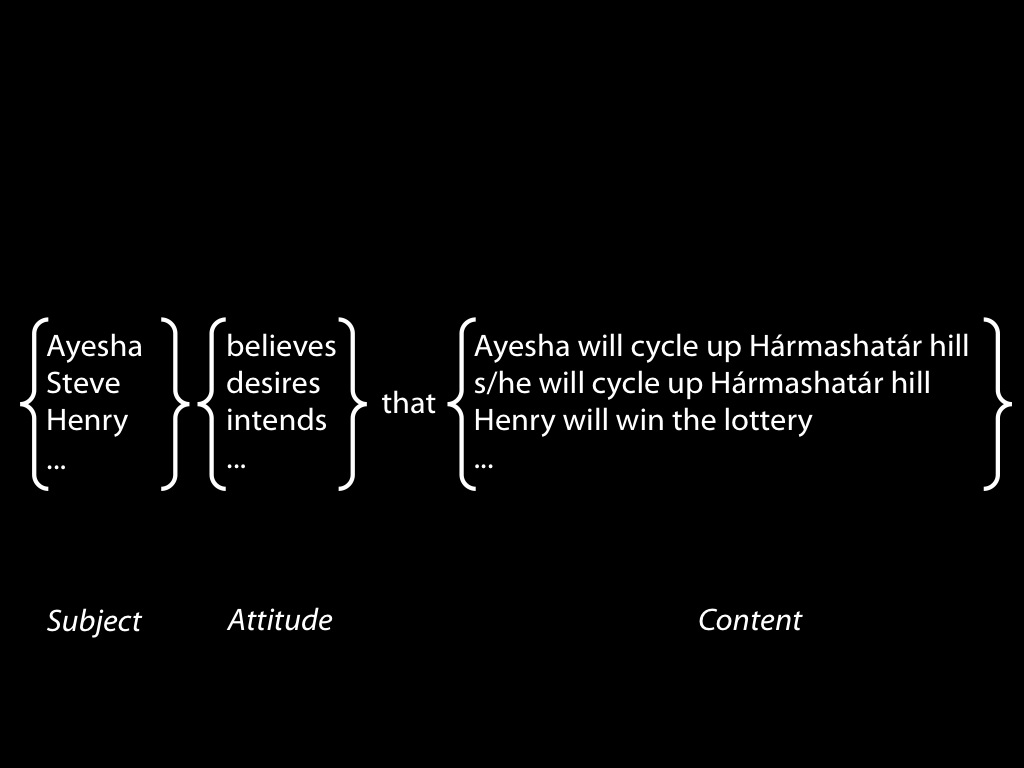

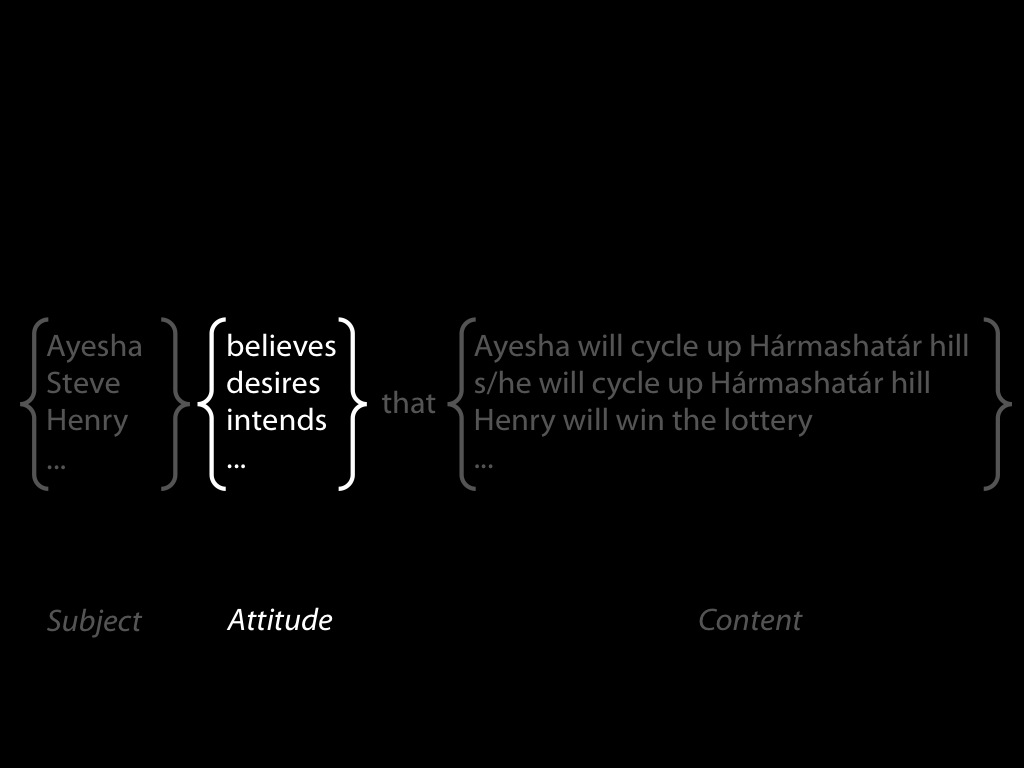

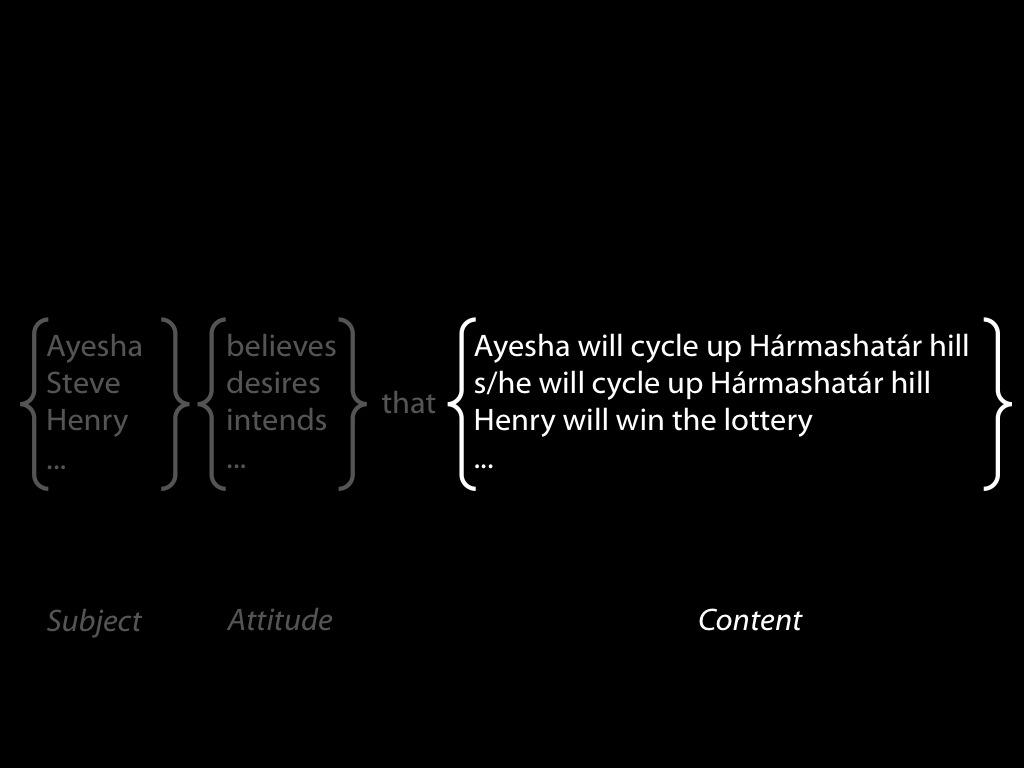

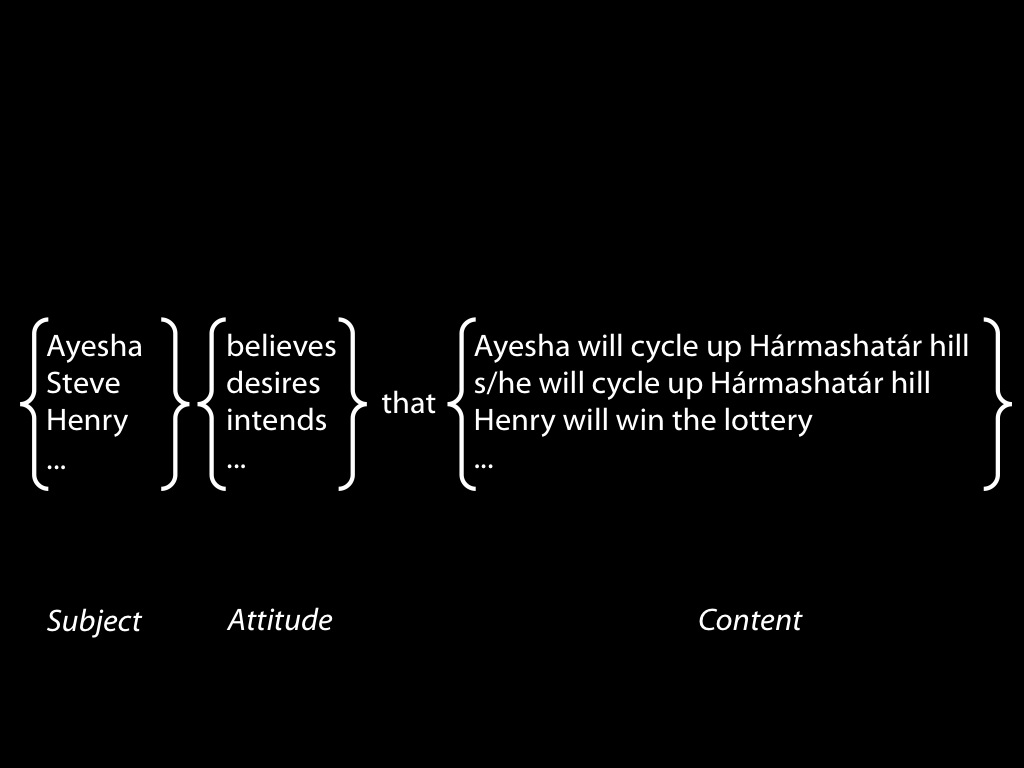

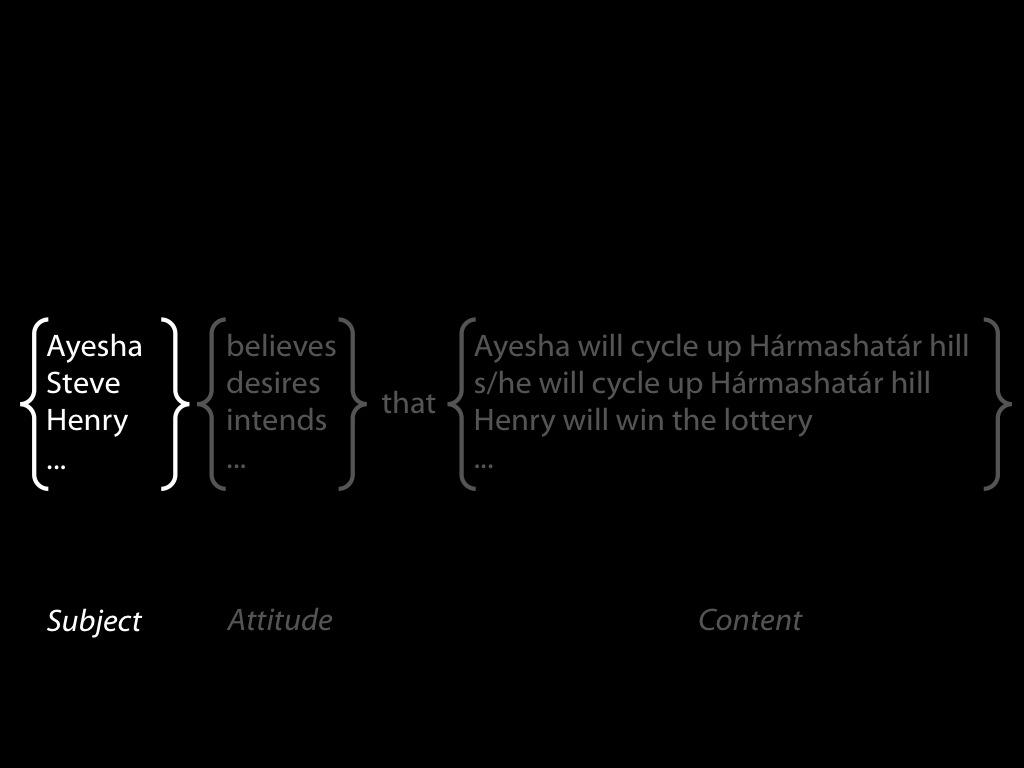

shared intention