Bratman offers a counterexample to something related to the Simple View \citep[see][]{Bratman:1992mi,bratman:2014_book}.

Suppose that you and I each intend that we, you and I, go to New York together.

But your plan is to point a gun at me and bundle me into the boot (or trunk) of your

car.

Then you intend that we go to New York together, but in a way that doesn't

depend on my intentions. As you see things, I'm going to New York with you whether

I like it or not. Does this provide the basis for an objection to the Simple View?

The Simple View

Two or more agents perform an intentional joint action

exactly when there is an act-type, φ, such that

each agent intends that

they, these agents, φ together

and their intentions are appropriately related to their actions.

Here’s the simple view again. My aim now is to present the most convincing objection

to it that I can.

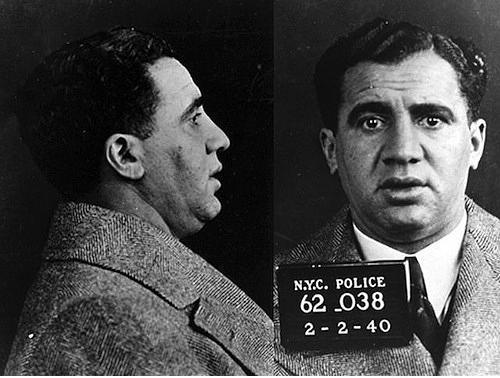

Bratman’s ‘mafia case’

Michael Bratman offers a counterexample to something related to the Simple View.

Suppose that you and I each intend that we, you and I, go to New York together.

But your plan is to point a gun at me and bundle me into the boot (or trunk) of your

car.

Then you intend that we go to New York together, but in a way that doesn't

depend on my intentions. As you see things, I'm going to New York with you whether

I like it or not. This doesn't seem like the basis for shared agency.

After all, your plan involves me being abducted.

But it is still a case in which we each intend that we go to New York together and we do.

So, apparently, the conditions of the Simple View are met (or almost met) and yet there is

no shared agency.

1. I intend that we, you and I, go to NYC together.

2. You intend that we, you and I, go to NYC together.

3. You intend that we, you and I, go to NYC together by way of you forcing me into the back of my car.

We’re considering that Bratman’s ‘mafia case’ provides a counterexample to

the Simple View. But does it really?

The mafia case fails as a counterexample to the Simple View because if you go through

with your plan, my actions won’t be appropriately related to my intention.

And, on the other hand, if you don’t go through with your plan, that it is at best

unclear that your having had that plan matters for whether we have shared agency.

I suggest that what is wrong in the Mafia Case is not that the agent’s need further

intentions, but just that if their intentions don’t connect to their actions in the

right way then there won’t be intentional joint action.

But the mafia case fails as a counterexample to the Simple View because if you go through

with your plan, my actions won’t be appropriately related to my intention.

And, on the other hand, if you don’t go through with your plan, that it is at best

unclear that your having had that plan matters for whether we exercise shared agency.

Bratman uses the Mafia case to motivate adding further intentions to

those specified by the Simple View.

But I suggest that an alternative response to the Mafia case is no less adequate

and simpler: what is wrong in the Mafia Case is not that the agents need further

intentions, but just that, if they act as they intend, their intentions won’t

all be appropriately related to their actions.

So Bratman’s ‘mafia case’ is not a counterexample to the Simple View.

I note that Bratman is clearly aiming to identify intentions whose fulfilment

requires shared agency. But I don’t think this is necessary.

It seems to me that what matters is that the Simple View as a whole

distingiushes shared agency from parallel but merely individual agency,

not that it does so by way of fulfilment conditions of intentions.

Rather than continuing to discuss whether the Mafia case really motivates rejecting

the Simple View, let me consider other ways to generate what seem to be more

plausible candidates for counterexamples to the Simple View ...