Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Sharing a Smile

Development of Joint Action: Planning

Objection: ‘Despite the common impression that joint action needs to be dumbed down for infants due to their ‘‘lack of a robust theory of mind’’ ... all the important social-cognitive building blocks for joint action appear to be in place: 1-year-old infants understand quite a bit about others’ goals and intentions and what knowledge they share with others’

‘I ... adopt Bratman’s (1992) influential formulation of joint action or shared cooperative activity. Bratman argued that in order for an activity to be considered shared or joint each partner needs to intend to perform the joint action together ‘‘in accordance with and because of meshing subplans’’ (p. 338) and this needs to be common knowledge between the participants’

Carpenter, 2009

‘shared intentional agency [i.e. ‘joint action’] consists, at bottom, in interconnected planning’

Bratman, 2011 p. 11

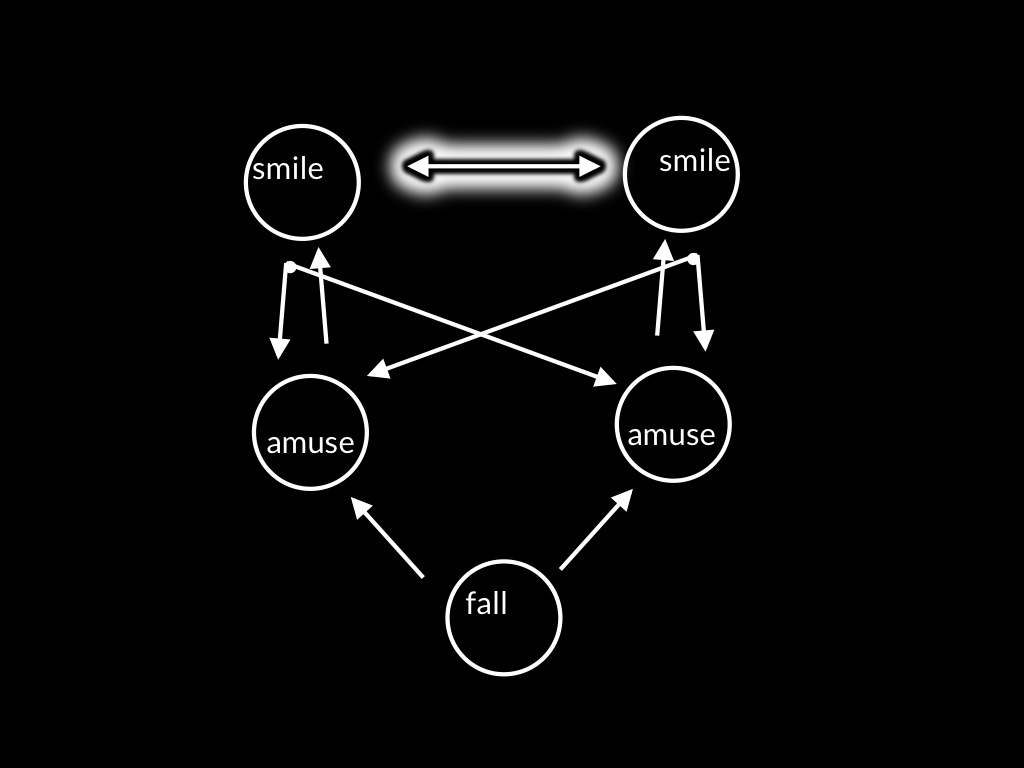

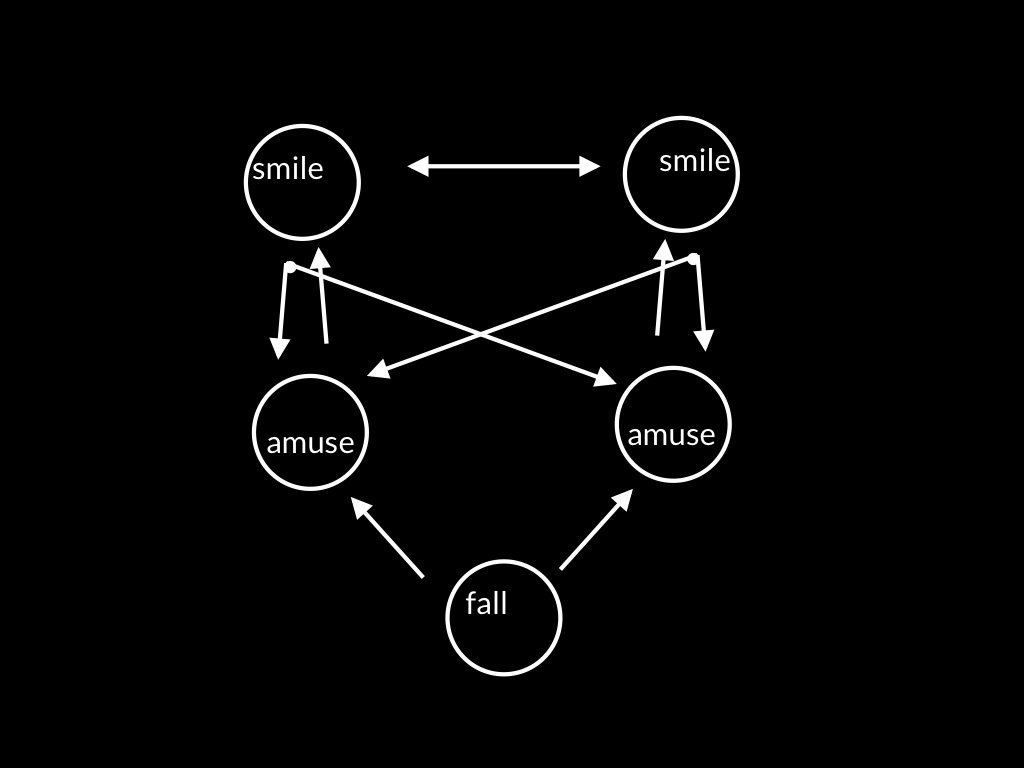

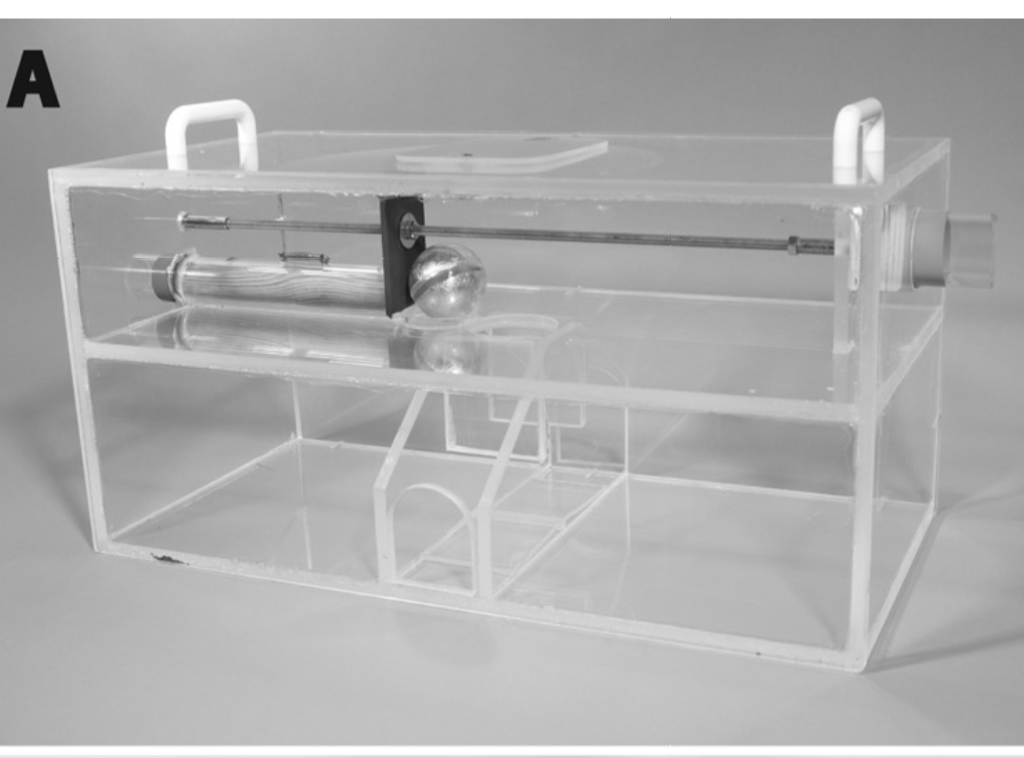

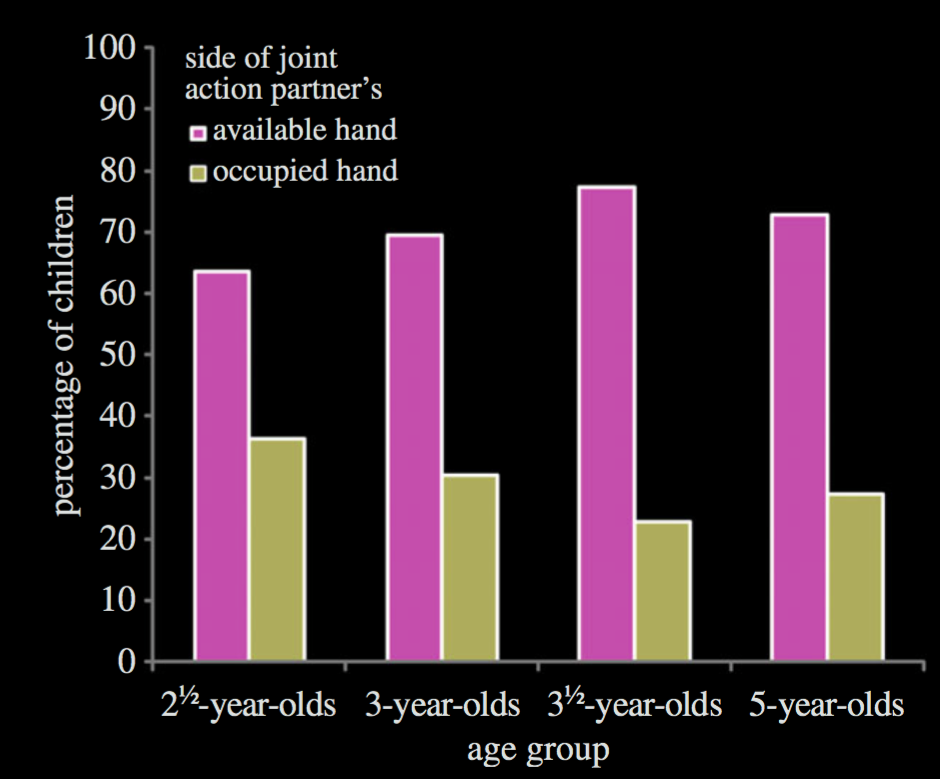

Paulus et al, 2016 figure 1

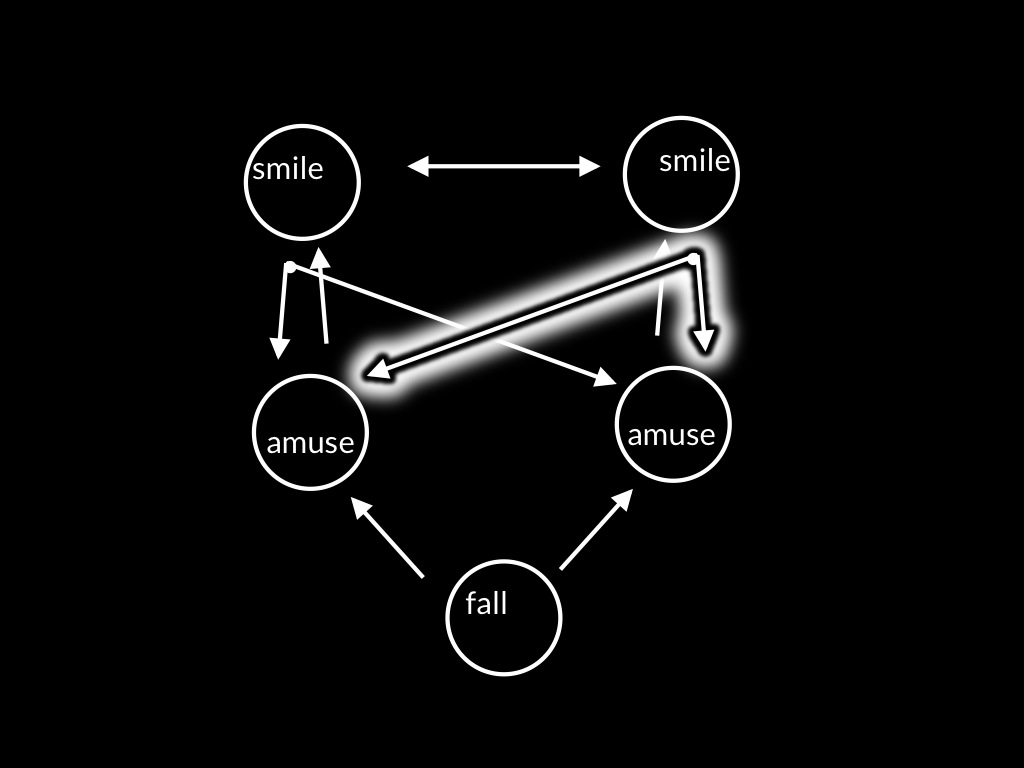

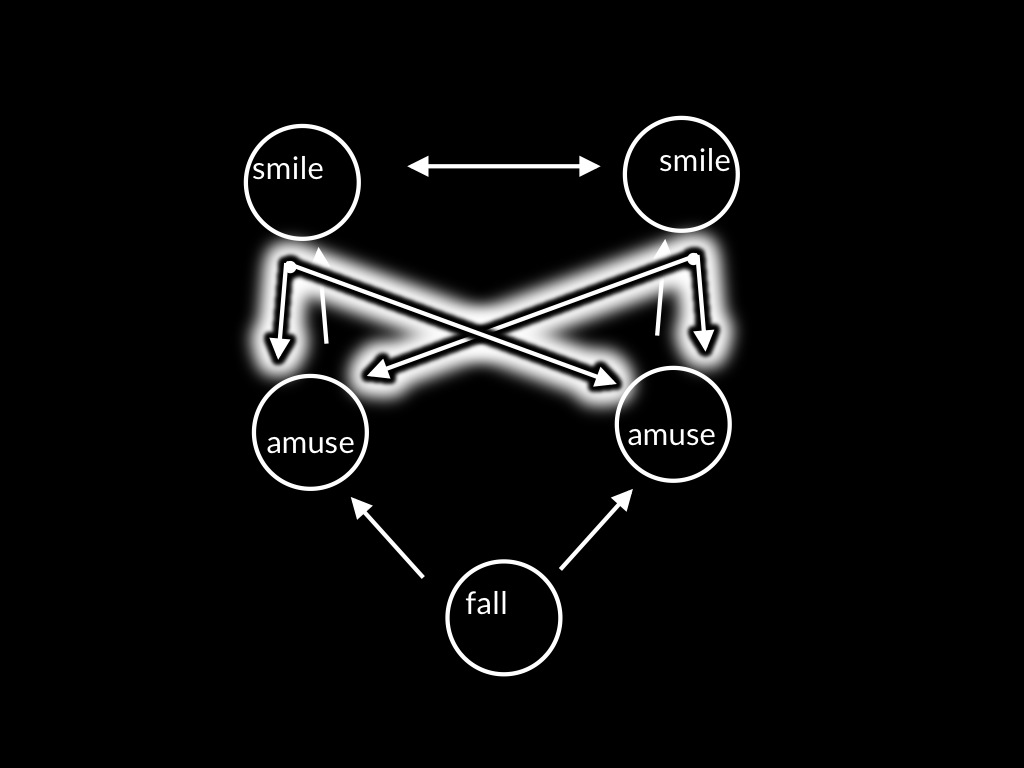

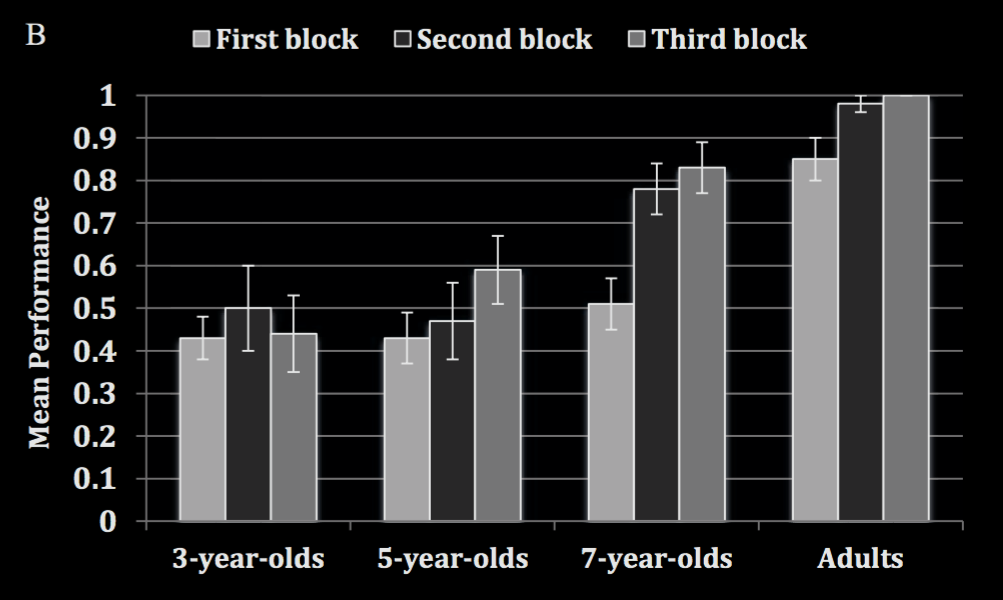

Paulus et al, 2016 figure 2B

‘3- and 5-year-old children do not consider another person’s actions in their own action planning (while showing action planning when acting alone on the apparatus).

Seven-year-old children and adults however, demonstrated evidence for joint action planning. ... While adult participants demonstrated the presence of joint action planning from the very first trials onward, this was not the case for the 7-year-old children who improved their performance across trials.’

Paulus et al, 2016 p. 1059

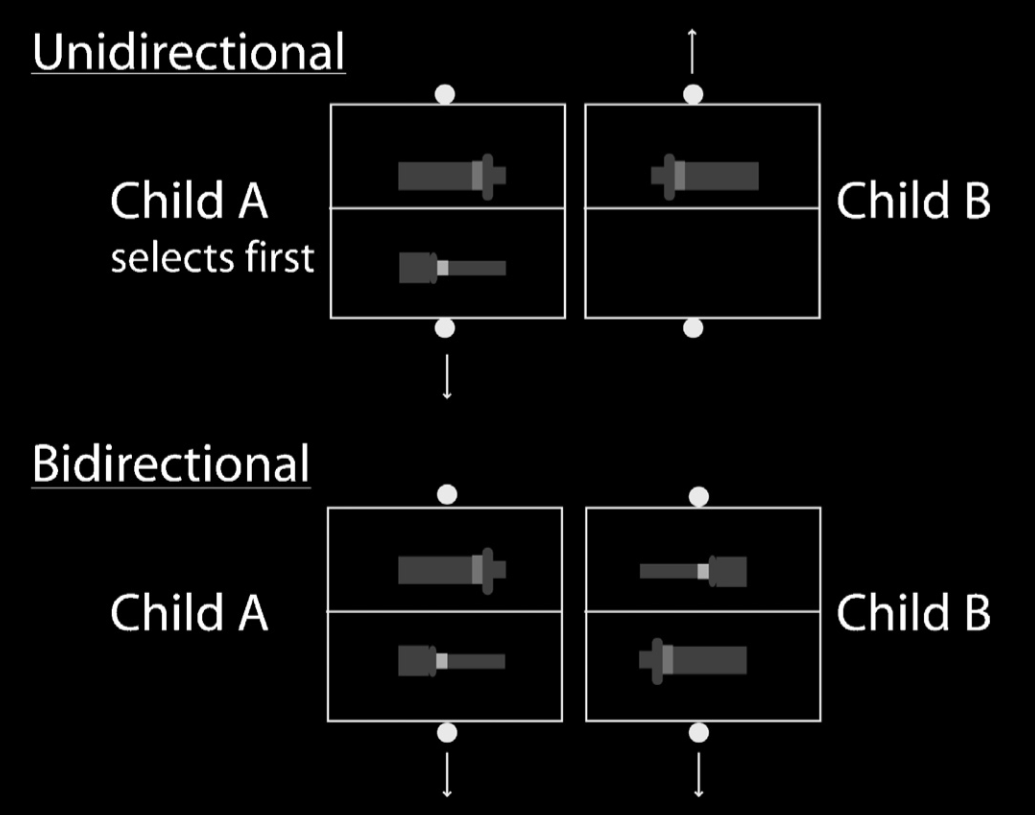

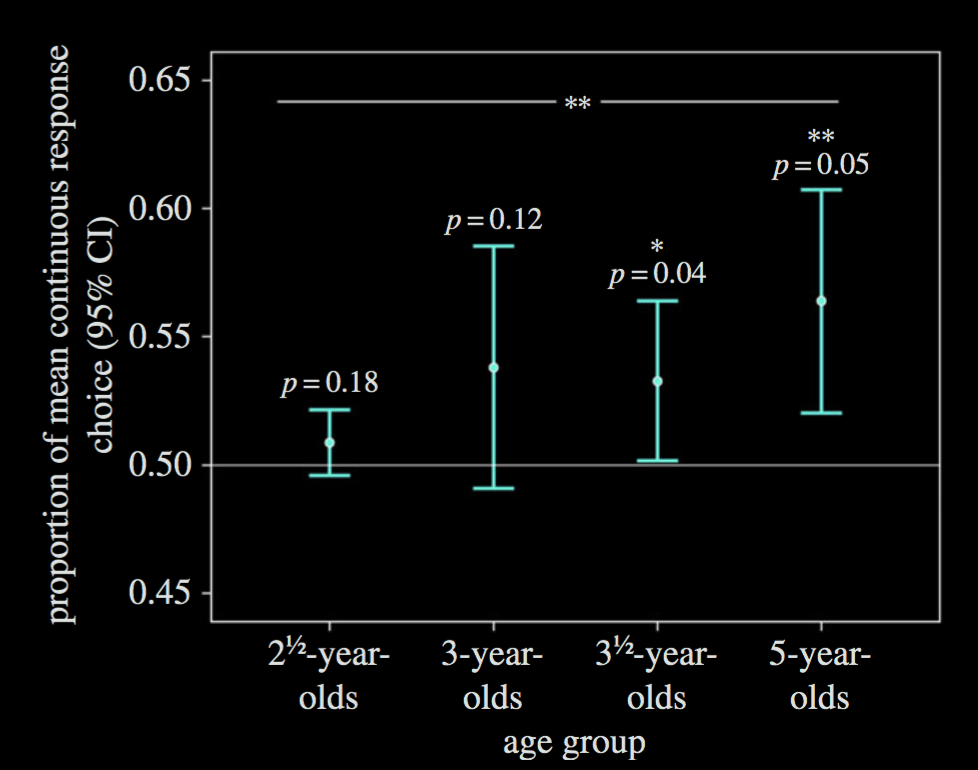

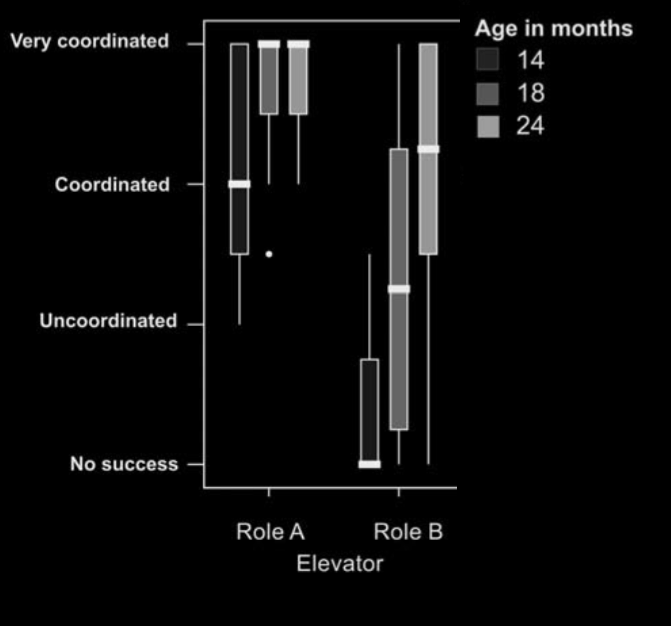

Warneken et al, 2014 figure 1A

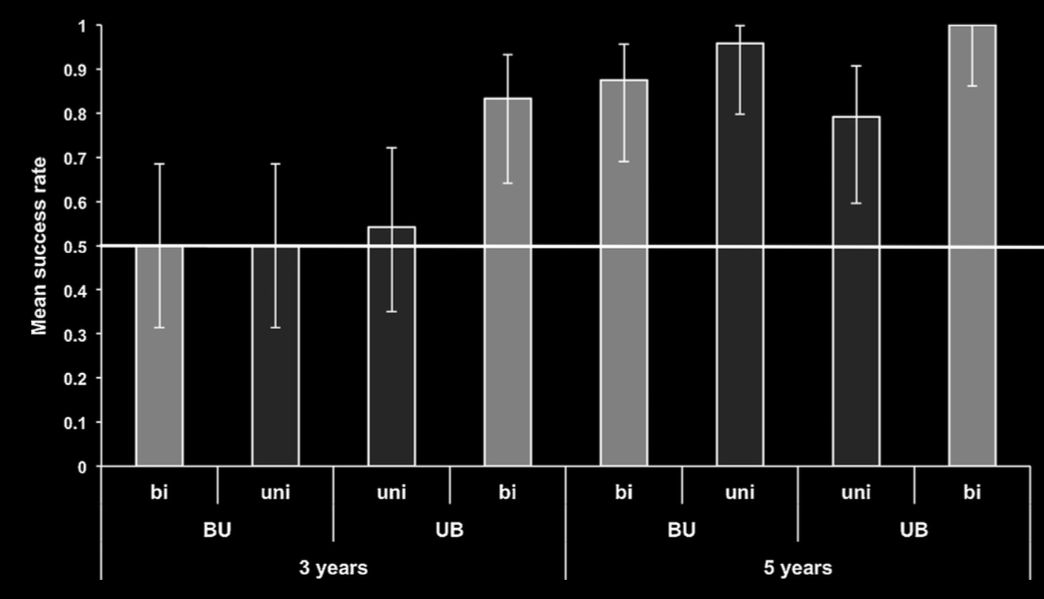

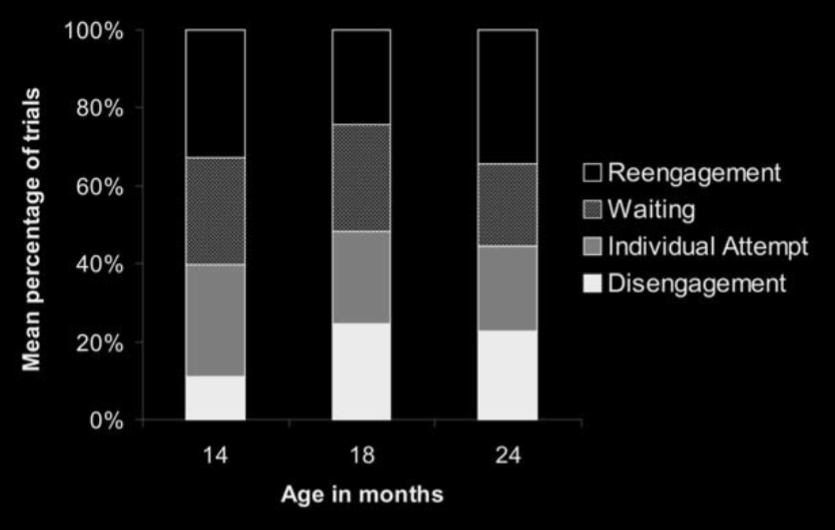

Warneken et al, 2014 figure 2

Warneken et al, 2014 figure 3

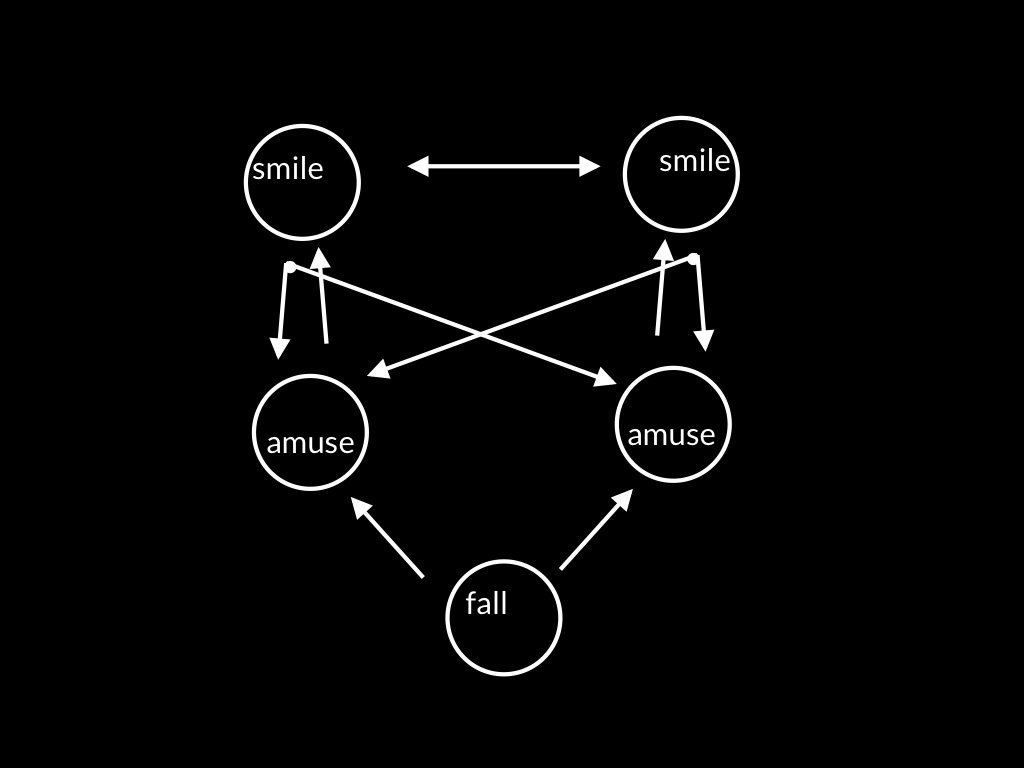

What is shared intention?

Functional characterisation:

shared intention serves to (a) coordinate activities, (b) coordinate planning and (c) structure bargaining

Constraint:

Inferential integration... and normative integration (e.g. agglomeration)

Substantial account:

We have a shared intention that we J if

‘1. (a) I intend that we J and (b) you intend that we J

‘2. I intend that we J in accordance with and because of la, lb, and meshing subplans of la and lb; you intend [likewise] …

‘3. 1 and 2 are common knowledge between us’

(Bratman 1993: View 4)

Mismatch:

Bratman’s account of joint action

vs

1- to 3-year-olds’ joint action abilities

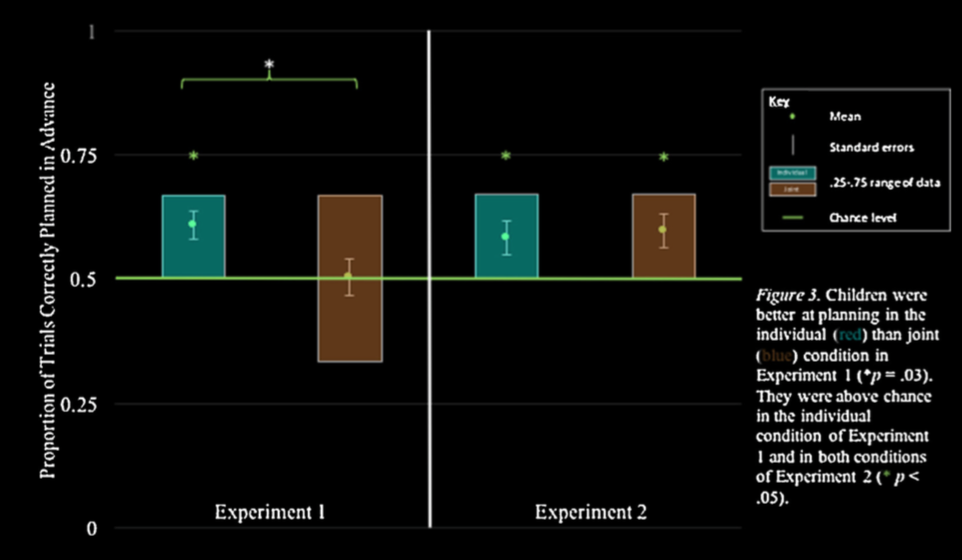

Meyer et al, 2016 figure 1A

Meyer et al, 2016 figure 1B

Meyer et al, 2016 figure 1C

Meyer et al, 2016 figure 2

Meyer et al, 2016 figure 3

Mismatch:

Bratman’s account of joint action

vs

1- to 3-year-olds’ joint action abilities

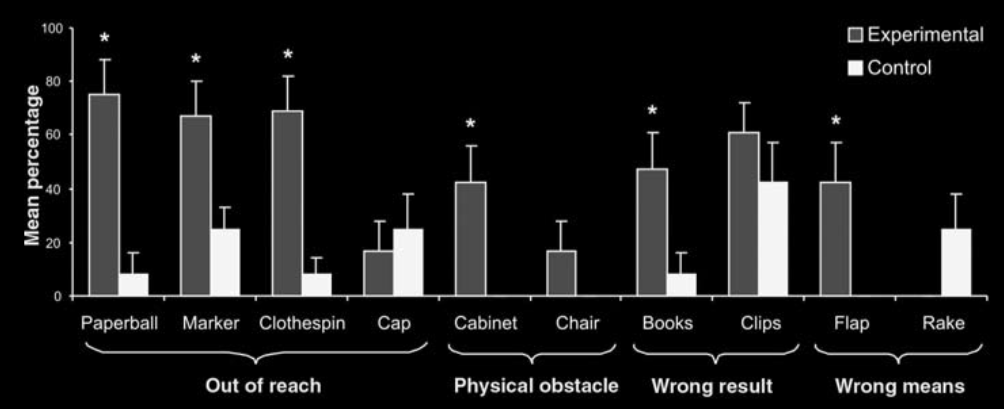

Gerson et al, 2016 figure 1B

Gerson et al, 2016 figure 3

How does Gerson et al’s study bear on the claim that Bratman’s account of shared intention and joint action characterises the social interactions children perform in the first two years of life?

What is shared intention?

Functional characterisation:

shared intention serves to (a) coordinate activities, (b) coordinate planning and (c) structure bargaining

Constraint:

Inferential integration... and normative integration (e.g. agglomeration)

Substantial account:

We have a shared intention that we J if

‘1. (a) I intend that we J and (b) you intend that we J

‘2. I intend that we J in accordance with and because of la, lb, and meshing subplans of la and lb; you intend [likewise] …

‘3. 1 and 2 are common knowledge between us’

(Bratman 1993: View 4)

Objection: ‘Despite the common impression that joint action needs to be dumbed down for infants due to their ‘‘lack of a robust theory of mind’’ ... all the important social-cognitive building blocks for joint action appear to be in place: 1-year-old infants understand quite a bit about others’ goals and intentions and what knowledge they share with others’

‘I ... adopt Bratman’s (1992) influential formulation of joint action or shared cooperative activity. Bratman argued that in order for an activity to be considered shared or joint each partner needs to intend to perform the joint action together ‘‘in accordance with and because of meshing subplans’’ (p. 338) and this needs to be common knowledge between the participants’

Carpenter, 2009

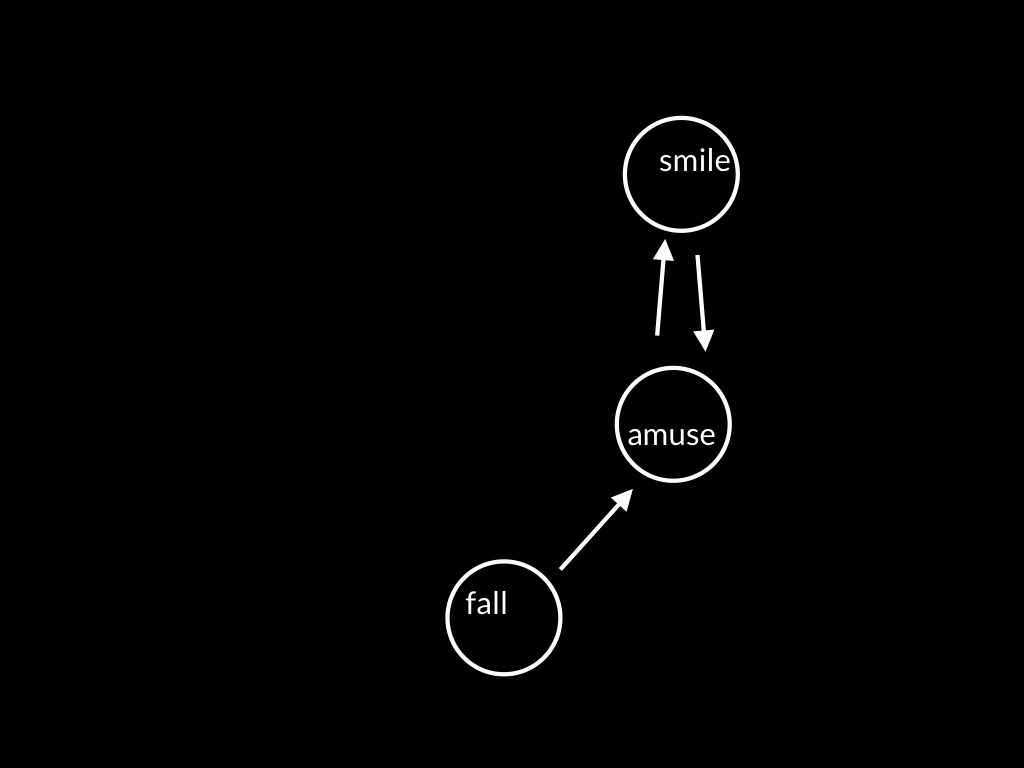

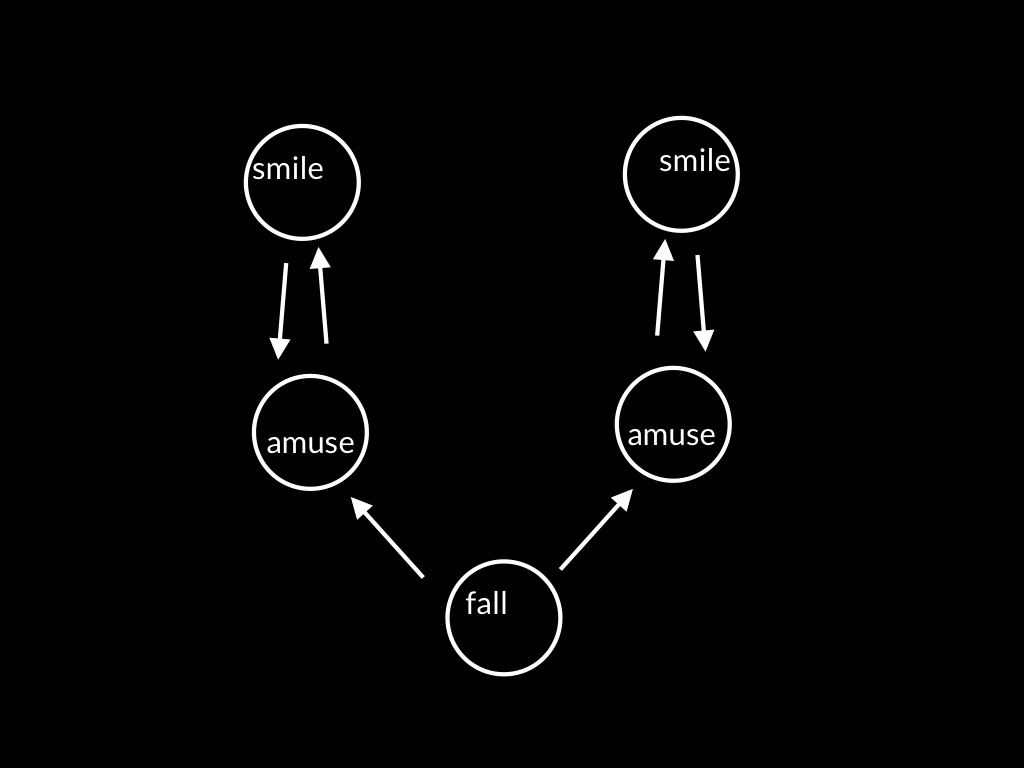

Development of Joint Action: Years 1-2

No planning ...

... So which joint actions can one- and two-year-olds perform?

‘By 12–18 months, infants are beginning to participate in a variety of joint actions which show many of the characteristics of adult joint action.’

Carpenter, 2009 p. 388

4-6 months

dyadic interactions

6-12 months

triadic interactions

~ 12-24 months

infants initiate and re-start joint actions

e.g. ‘peek-a-boo; tickle; rhythmic games; chase’

Brownell, 2011

drumming together

(from two years of age; Endedijk et al, 2015)

Warneken and Tomasello, 2006

Warneken and Tomasello, 2006

Warneken and Tomasello, 2006

Warneken and Tomasello, 2007 figure 2 (part)

Warneken and Tomasello, 2007 figure 3 (part)

Warneken and Tomasello, 2007 figure 2 (part)

Warneken and Tomasello, 2007 figure 4

Infants’ ‘attempts to reactivate the partner in interruption periods indicate that they were aware of the interdependency of actions—that the execution of their own actions was conditional on that of the partner’

‘these instances might also exemplify a basic understanding of shared intentionality’

Warneken and Tomasello, 2007 pp. 290-1

Joint Action in Years 1-2

In the first and second years of life,

there is joint action

but it does not appear to involve planning agency

or shared intention.

Bratman’s account does not characterise

the sort of joint actions

infants perform in the first and second years of life.

Two-year-olds perform some joint actions but not others.

What distinguishes the joint actions they can perform from those they cannot?