Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

‘participation in cooperative ... interactions … leads children to construct uniquely powerful forms of cognitive representation.’

(Moll & Tomasello 2007)

‘perception, action, and cognition are grounded in social interaction’

(Knoblich & Sebanz 2006)

‘human cognitive abilities … [are] built upon social interaction’

(Sinigaglia and Sparaci 2008)

What kinds of social interaction? Joint actions!

(a) All joint action involves shared intention.

(b) Bratman is right about shared intention.

Carpenter(2009, p. 281)

We have a shared intention that we J if

‘1. (a) I intend that we J and (b) you intend that we J

‘2. I intend that we J in accordance with and because of la, lb, and meshing subplans of la and lb; you intend [likewise] …

‘3. 1 and 2 are common knowledge between us’

(Bratman 1993: View 4)

Functional characterisation:

shared intention serves to (a) coordinate activities, (b) coordinate planning and (c) structure bargaining

Substantial account:

We have a shared intention that we J if

‘1. (a) I intend that we J and (b) you intend that we J

‘2. I intend that we J in accordance with and because of la, lb, and meshing subplans of la and lb; you intend [likewise] …

‘3. 1 and 2 are common knowledge between us’

(Bratman 1993: View 4)

1. joint action fosters an understanding of minds;

2. all joint action involves shared intention; and

3. a function of shared intention is to coordinate two or more agents’ plans.

Bratman already refuted? No. But we need more.

A Counterexample to Bratman

Having a shared intention involves us each intending that we, you and I, φ together.

Bratman

‘Bratman’s account presupposes the element of sharedness it aims to explain.’

‘It is only because we intend to J that I can have intentions of the form “I intend that we J”’

‘Bratman’s ... account of shared intentionality ... fails to give an account of the crucial element of collectiveness that is presupposed at its very base’

Schmid (2009, p. 36)

Functional characterisation:

shared intention serves to (a) coordinate activities,

(b) coordinate planning, and

(c) structure bargaining

We have a shared intention that we J if

‘1. (a) I intend that we J and (b) you intend that we J

‘2. I intend that we J in accordance with and because of la, lb, and meshing subplans of la and lb; you intend [likewise] …

‘3. 1 and 2 are common knowledge between us’

(Bratman 1993: View 4)

Blomberg (personal communication)

Is it a counterexample?

[btw] A counterexample to the sufficiency of Bratman’s conditions for shared intention is also a counterexample to the Simple View.

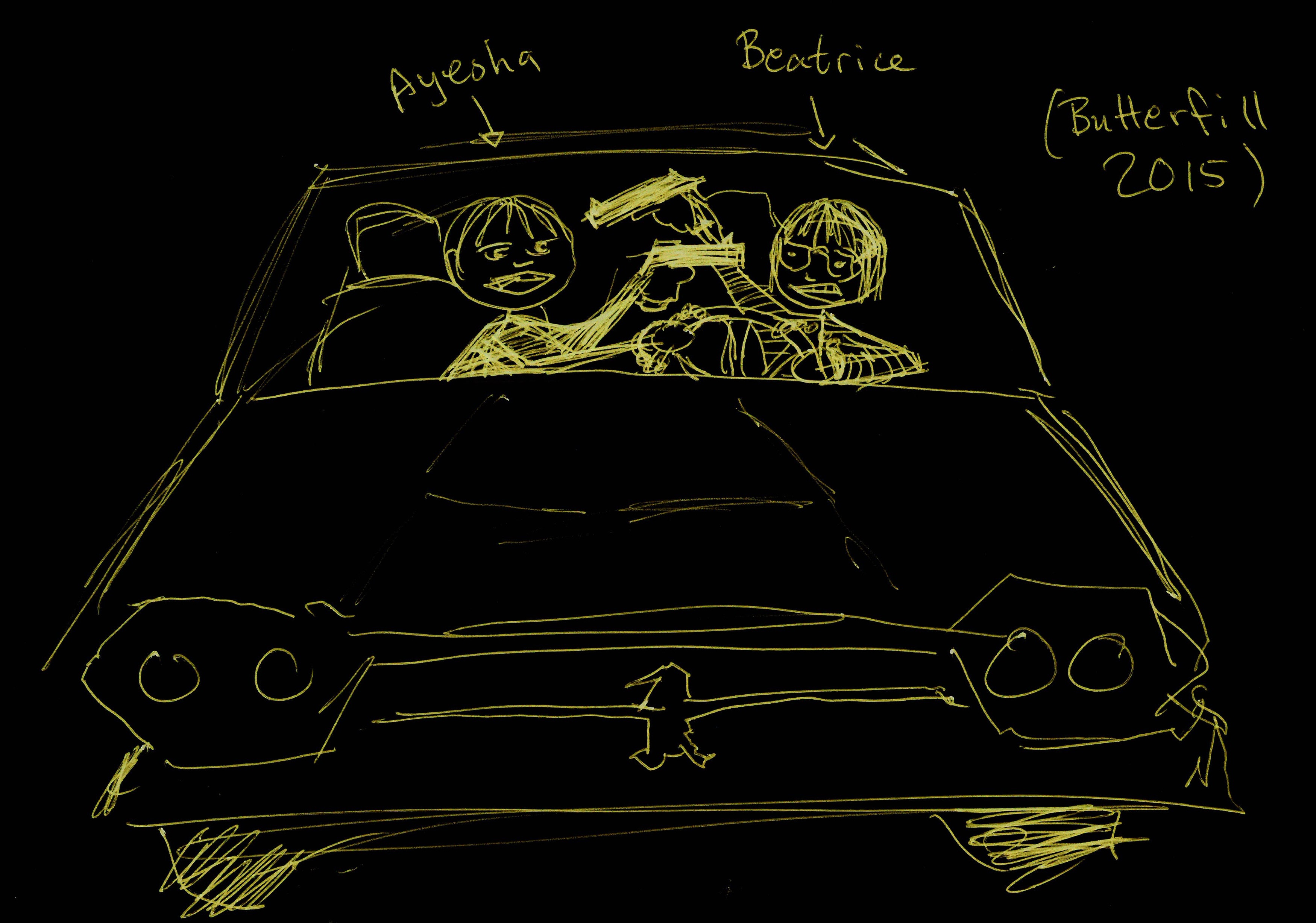

a second attempt

We have an unshared intention that we <J1, J2> iff

‘1. (a) I intend that we J1 and (b) you intend that we J2

‘2. I intend that we J1in accordance with and because of la, lb, and meshing subplans of la and lb; you intend [likewise] …

‘3. 1 and 2 are common knowledge between us’

We have a shared intention that we J if

‘1. (a) I intend that we J and (b) you intend that we J

‘2. I intend that we J in accordance with and because of la, lb, and meshing subplans of la and lb; you intend [likewise] …

‘3. 1 and 2 are common knowledge between us’

(Bratman 1993: View 4)

| true? | A&A make use of? | |

| Ayesha intends J1 | ✓ | ✓ |

| Ahmed intends J2 | ✓ | ✓ |

| J1=J2 | ✗ | ✗ |

| true? | B&B make use of? | |

| Beatrice intends J1 | ✓ | ✓ |

| Baldric intends J2 | ✓ | ✓ |

| J1=J2 | ✓ | ✗ |

Joint Action

Parallel but Merely Individual Action

Two people making the cross hit the red square in the ordinary way.

Beatrice & Baldric’s making the cross hit the red square

Two sisters cycling together.

Two strangers cycling the same route side-by-side.

Members of a flash mob simultaneously open their newspapers noisily.

Onlookers simultaneously open their newspapers noisily.

We have a shared intention that we J if

‘1. (a) I intend that we J and (b) you intend that we J

‘2. I intend that we J in accordance with and because of la, lb, and meshing subplans of la and lb; you intend [likewise] …

‘3. 1 and 2 are common knowledge between us’

(Bratman 1993: View 4)

‘each agent does not just intend that the group perform the […] joint action.

‘Rather, each agent intends as well that the group perform this joint action in accordance with subplans (of the intentions in favor of the joint action) that mesh’

(Bratman 1992: 332)

conclusion

- Given a conjecture about development, Bratman’s account cannot be the whole story about joint action.

- There is a (putative) counterexample to Bratman’s account

so?

ps

Is Common Knowledge Necessary?

What is shared intention?

Substantial account:

We have a shared intention that we J if

‘1. (a) I intend that we J and (b) you intend that we J

‘2. I intend that we J in accordance with and because of la, lb, and meshing subplans of la and lb; you intend [likewise] …

‘3. 1 and 2 are common knowledge between us’

(Bratman 1993: View 4)

‘Miller (2001, 60) submits that ‘mutual knowledge is what distinguishes joint action from interdependent action that is not joint’, but never explains why mutual knowledge has this transformative power’

Blomberg, 2015 p. 3

Why common knowledge?

Facts about your intentions feature in my planning.

Only known facts can feature in my planning.

Therefore *knowledge* is required.

‘public access to the shared intention will normally be involved in further thought that is characteristic of shared intention, as when we plan together how to carry out our shared intention.’

Bratman (2015, p. 57)

What I intend depends on my knowledge of what you intend

... which depends on your knowledge of what I intend

... which depends on my knowledge of what you intend

...