Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

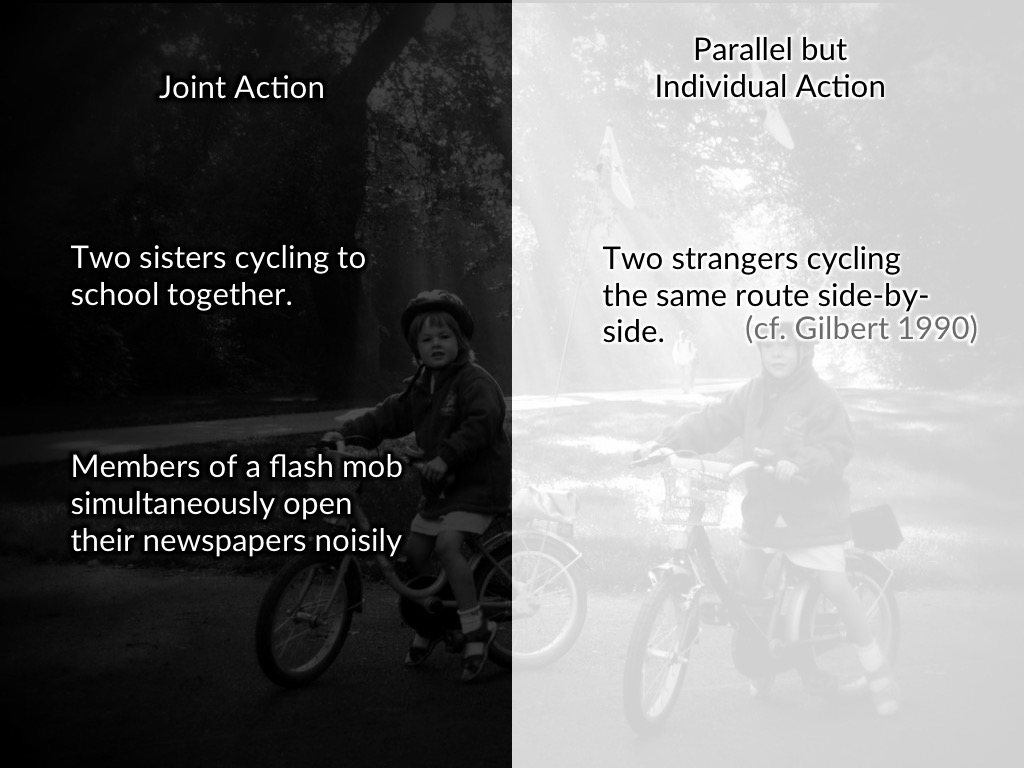

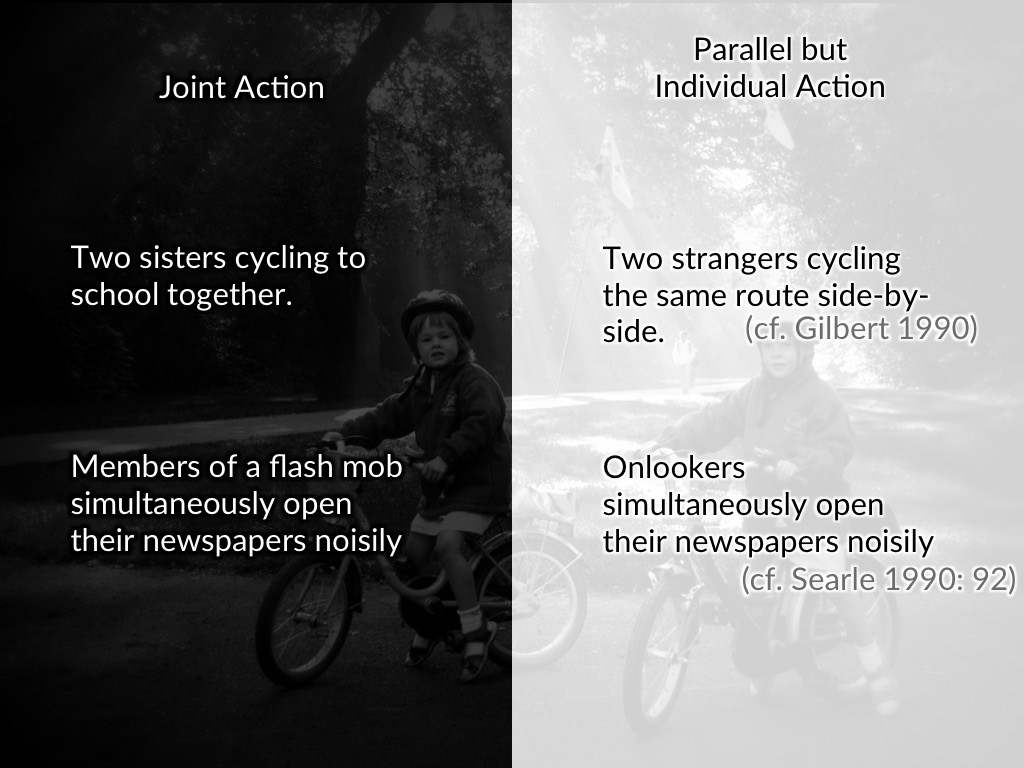

Give another contrast pair.

Question

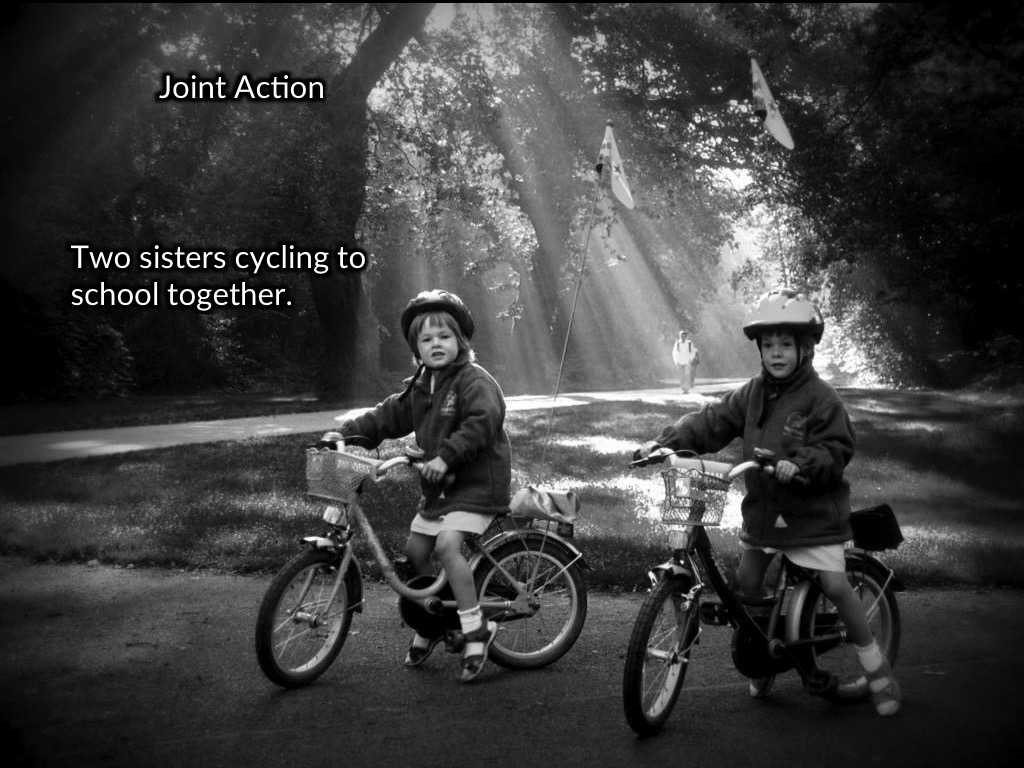

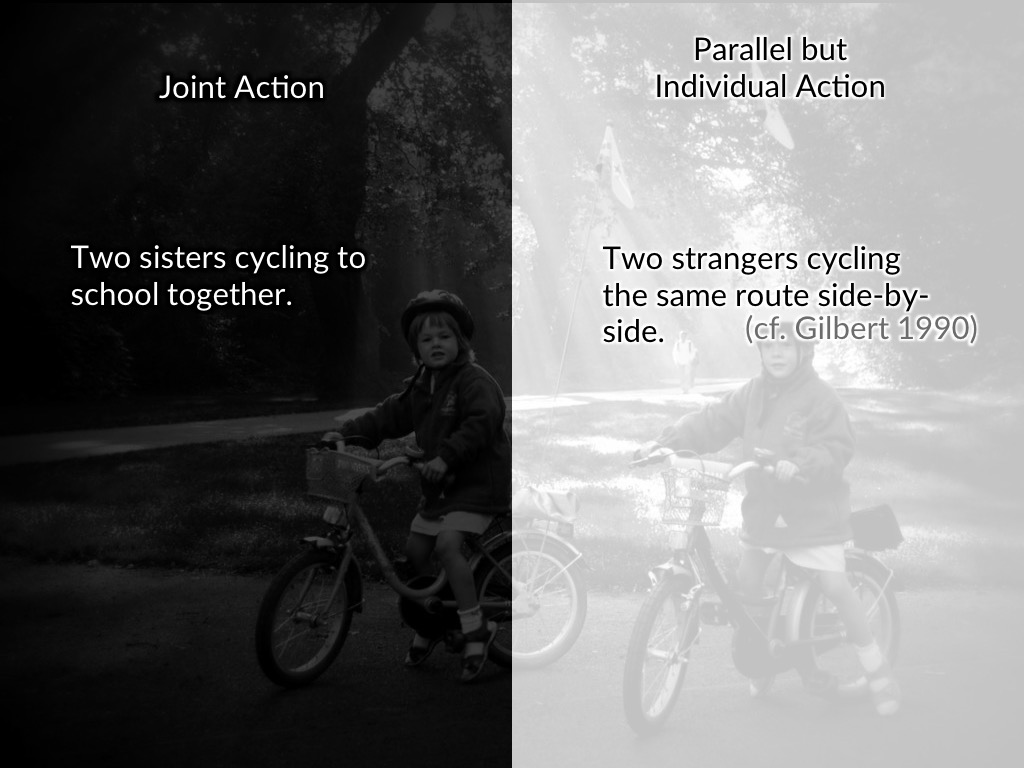

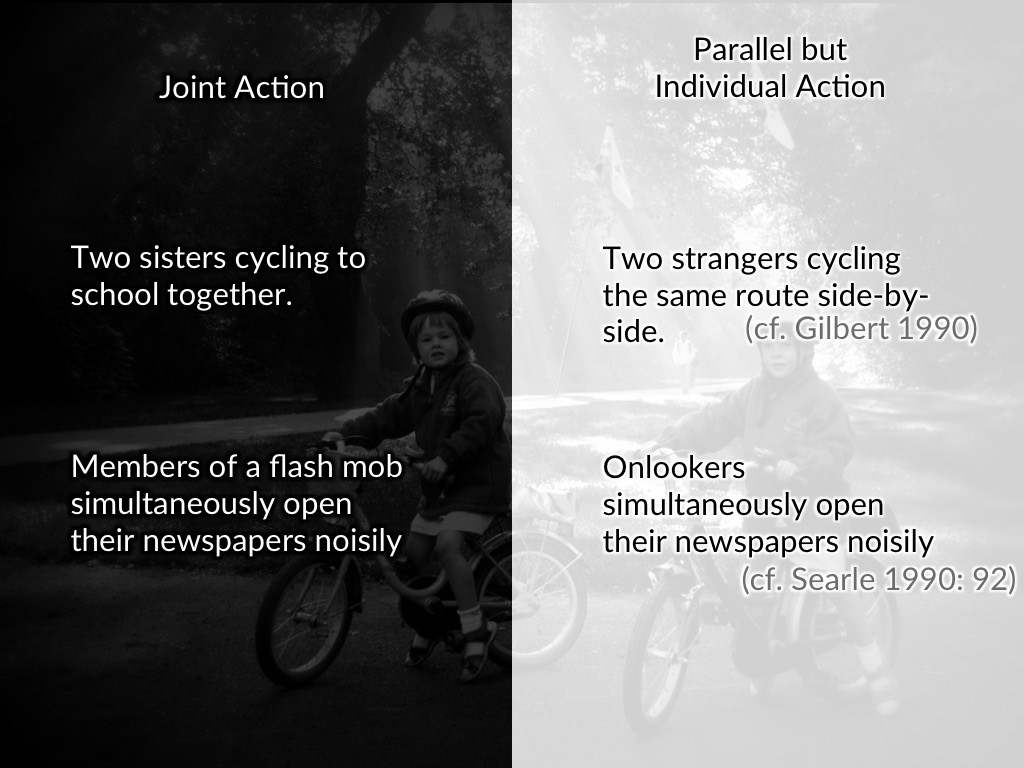

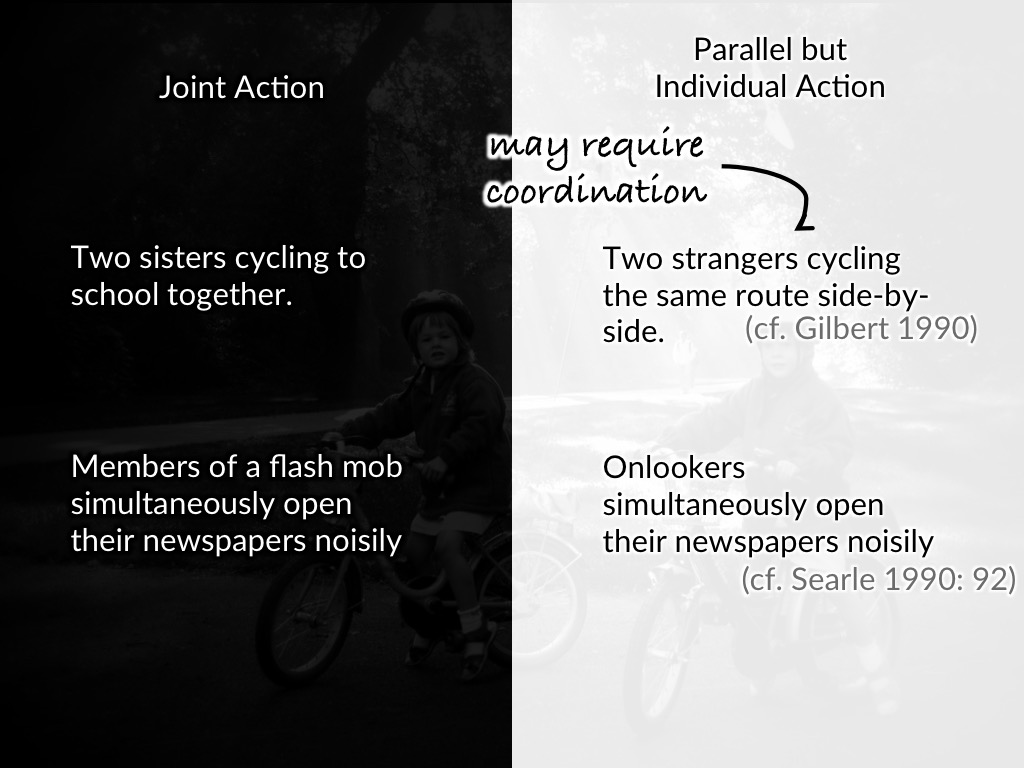

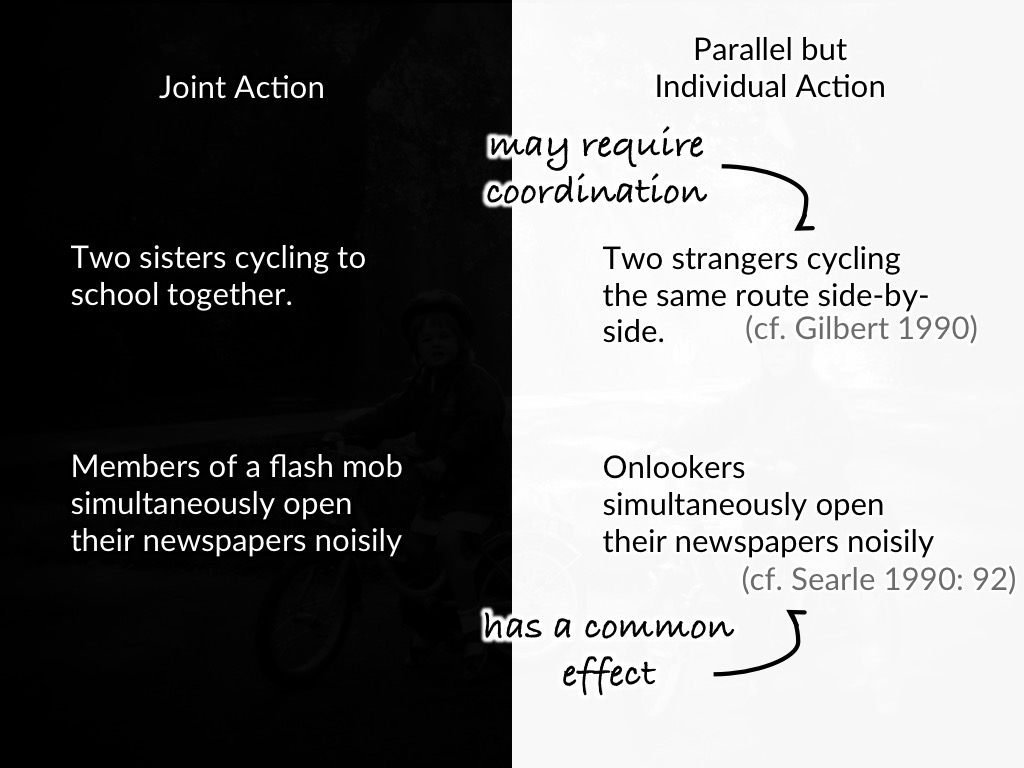

What distinguishes genuine joint actions from parallel but merely individual actions?

Requirement

An account of joint action must draw a line between joint actions and parallel but merely individual actions.

Aim

Which forms of shared agency underpin our social nature?

Individual vs Aggregate -- both miss shared agency

Admin

first writing task

https://yyrama.butterfill.com/course/view/JointActionBochum

Short (<501 words) writing assignment.

What is the Simple View? First carefully introduce the question about joint action to which the Simple View is supposed to be an answer. Then introduce and evaluate an objection to it. ...

Also: provide a peer review of another student’s work.

The Simple View

We each intend that we, you and I, cycle to school together.

What distinguishes

an ordinary, individual action from a mere happening?

Your intention that you throw the coffee at me.

What distinguishes

genuine joint actions from parallel but merely individual actions?

Our intentions that we, you and I, cycle to school together.

The Simple View

Two or more agents perform an intentional joint action

exactly when there is an act-type, φ, such that

each agent intends that

they, these agents, φ together

and their intentions are appropriately related to their actions.

Objection?

The Circularity Objection

We each intend that we, you and I, cycle to school together.

‘[H]ow can an individual refer to a joint activity without the jointness [...] already being in place?’ (Schweikard and Schmid, 2013)

Contrast:

We each intend that we, you and I, cycle to school together.

We each intend that we, you and I, cycle to school apart.

acting together vs exercising shared agency

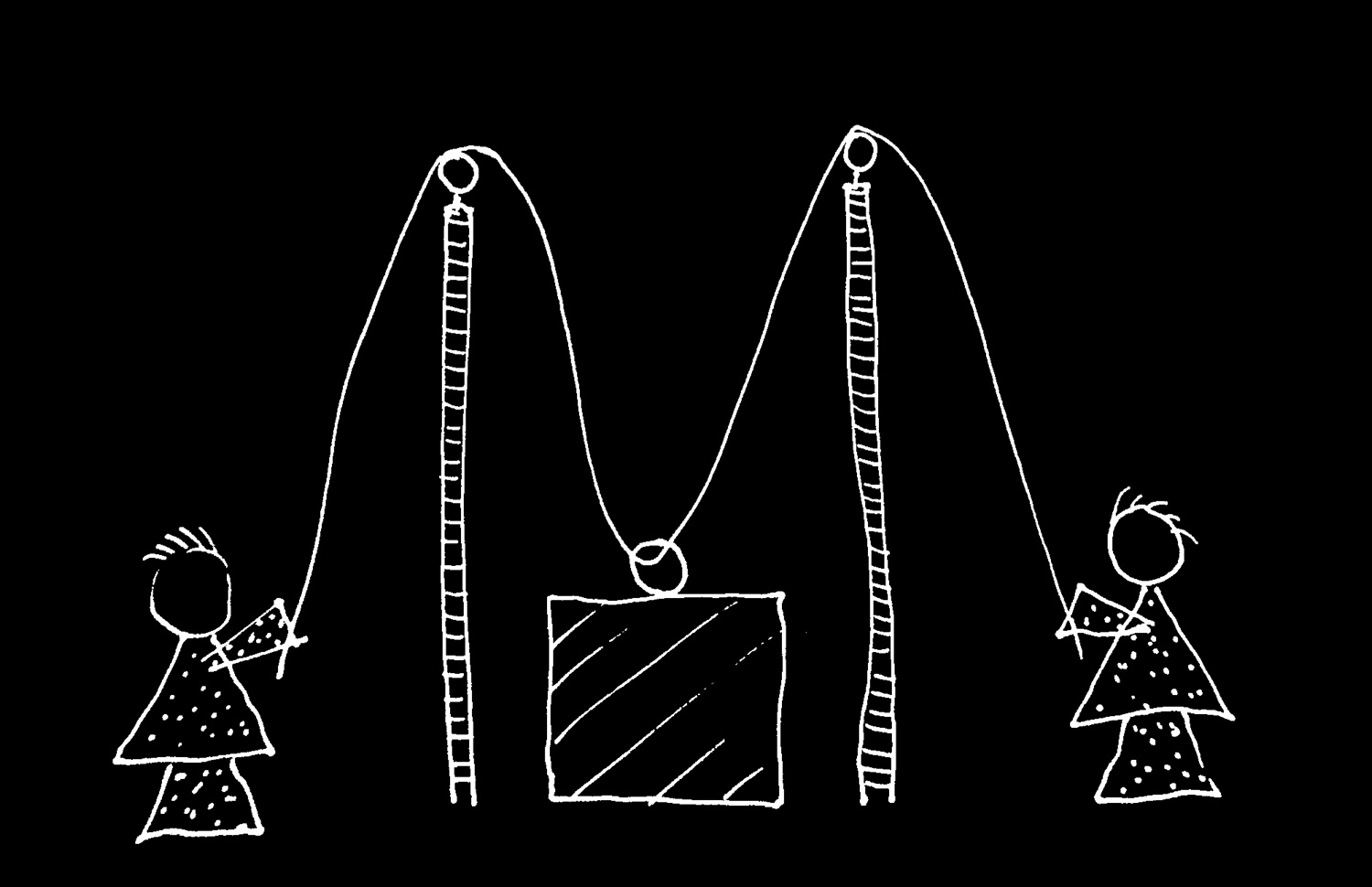

Are Ayesha and Beatrice

acting together?

Is Ayesha and Beatrice’s

lifting the block together

a joint action?

We each intend that we, you and I, cycle to school together.

‘[H]ow can an individual refer to a joint activity without the jointness [...] already being in place?’ (Schweikard and Schmid, 2013)

terminology:

shared agency

joint action

‘collective’ action / agency

---

acting together

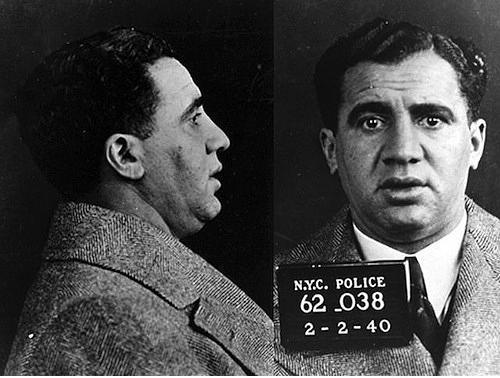

Walking Together in the Mafia Sense

The Simple View

Two or more agents perform an intentional joint action

exactly when there is an act-type, φ, such that

each agent intends that

they, these agents, φ together

and their intentions are appropriately related to their actions.

Bratman’s ‘mafia case’

1. I intend that we, you and I, go to NYC together.

2. You intend that we, you and I, go to NYC together.

3. You intend that we, you and I, go to NYC together by way of you forcing me into the back of my car.

conclusion

Objectives for this lecture:

- understand questions about shared agency

- can use the method of contrast cases

- familiar with the Simple View

- can critically assess objections to the Simple View [tbc]

Question

What distinguishes genuine joint actions from parallel but merely individual actions?

Requirement

An account of joint action must draw a line between joint actions and parallel but merely individual actions.

Aim

Which forms of shared agency underpin our social nature?