By way of giving you a preview of what is coming,

I want to explore a sequence of three four ideas.

1. An imaginary we ... that plays a guiding role ... and ends up not being imaginary after all

(List, Pettit, Helm, ...)

Objections: (a) seems to depend on long-term collaboration, or at least the potential for it;

(b) intellectualist (depends on members thinking of themselves as members of a group);

and (c) clearly involves the group as an entity distinct from any of the individuals.

2. Gilbert’s joint commitments to emulate a single body

3. Team reasoning ... and its relation to shared intention ‘lite’

(Gold & Sugden, Pacherie ...)

Advantages: (a) Less intellectualist; (b) doesn’t presuppose, but promises to explain shared intention.

Objections: (a) very limited model (decision theory and team reasoning);

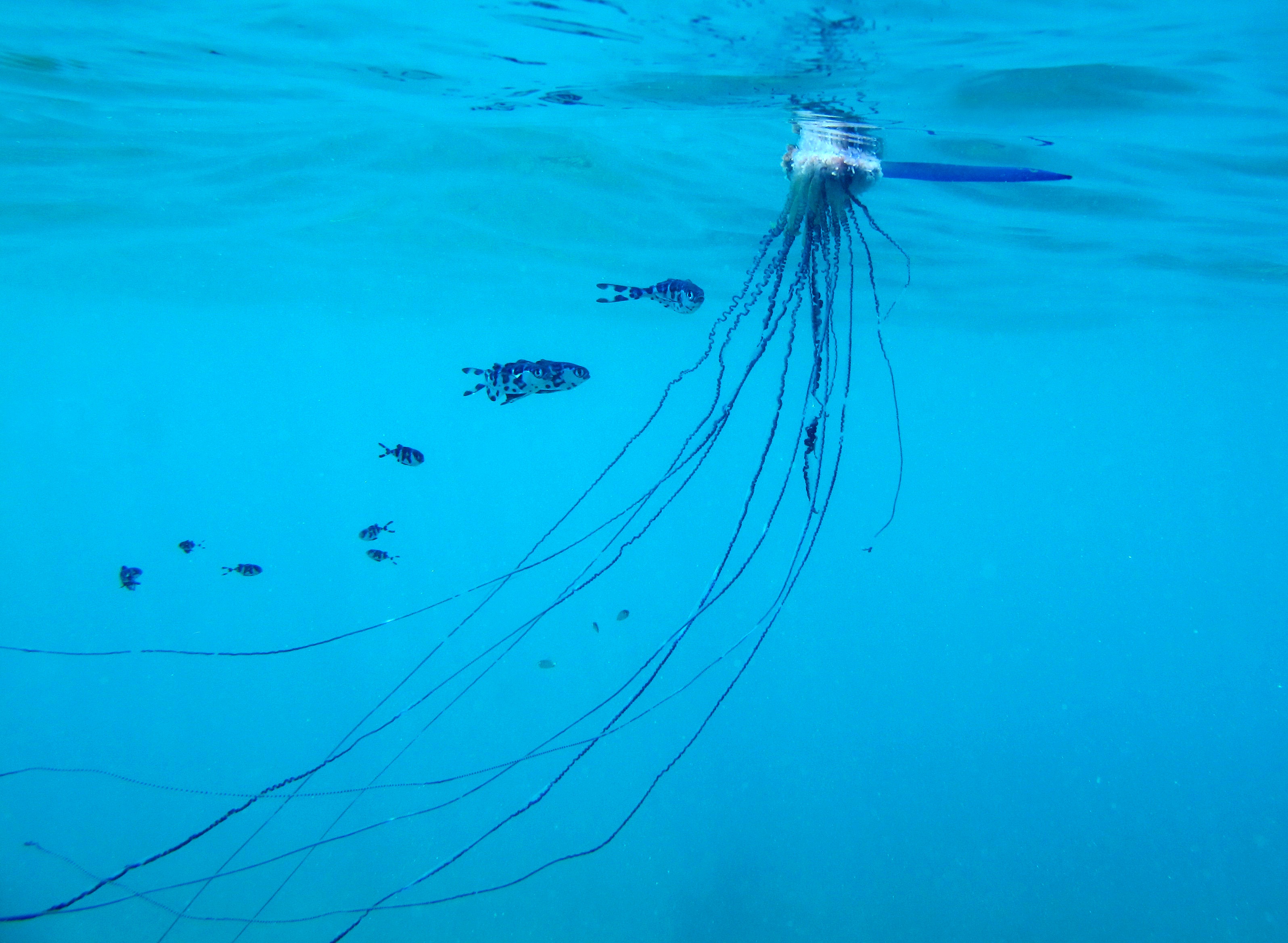

(b) requires frames (am I the jellyfish or a polyp today?)

(c) counterexamples to Pacherie (too ‘lite’)?

(d) Not ‘lite’ enough (depending on what intentions are),

(e) Still fails the requirements on inferential and normative integration of shared intentions with intentions.

Emphasise:

(b) requires frames (am I the jellyfish or a polyp today?)

‘participants in a joint action represent their partners as doing their parts in the same way as individual intentions implicitly represent the agent as continuing to be willing and able to perform the action until the intention’s conditions of satisfaction are reached (individual agents of temporally extended actions “represent” their own future intentions and actions in the same way in which cooperators represent their partners’ intentions and actions)’

\citep[p.~50]{Schmid:2013}

‘individual agents of temporally extended actions “represent” their own future intentions and actions

in the same way in which cooperators represent their partners’ intentions and actions’

Schmid (2013, p. 50)

Ultimately, there is a justification for postulating collecive intentions, collective commitments and the rest.

But the justification is that by self-ascribing such attitudes, individual agents may

achieve coordination and cooperation.

(Gilbert claims people happen to understand themselves in this way; but she has no

account at all of how understanding yourself in that way, or failing to, would make a

difference to the kickings, walkings and smiles that make up everyday social interactions.)