Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

The Circularity Objection

We each intend that we, you and I, cycle to school together.

‘[H]ow can an individual refer to a joint activity without the jointness [...] already being in place?’ (Schweikard and Schmid, 2013)

Contrast:

We each intend that we, you and I, cycle to school together.

We each intend that we, you and I, cycle to school apart.

acting together vs exercising shared agency

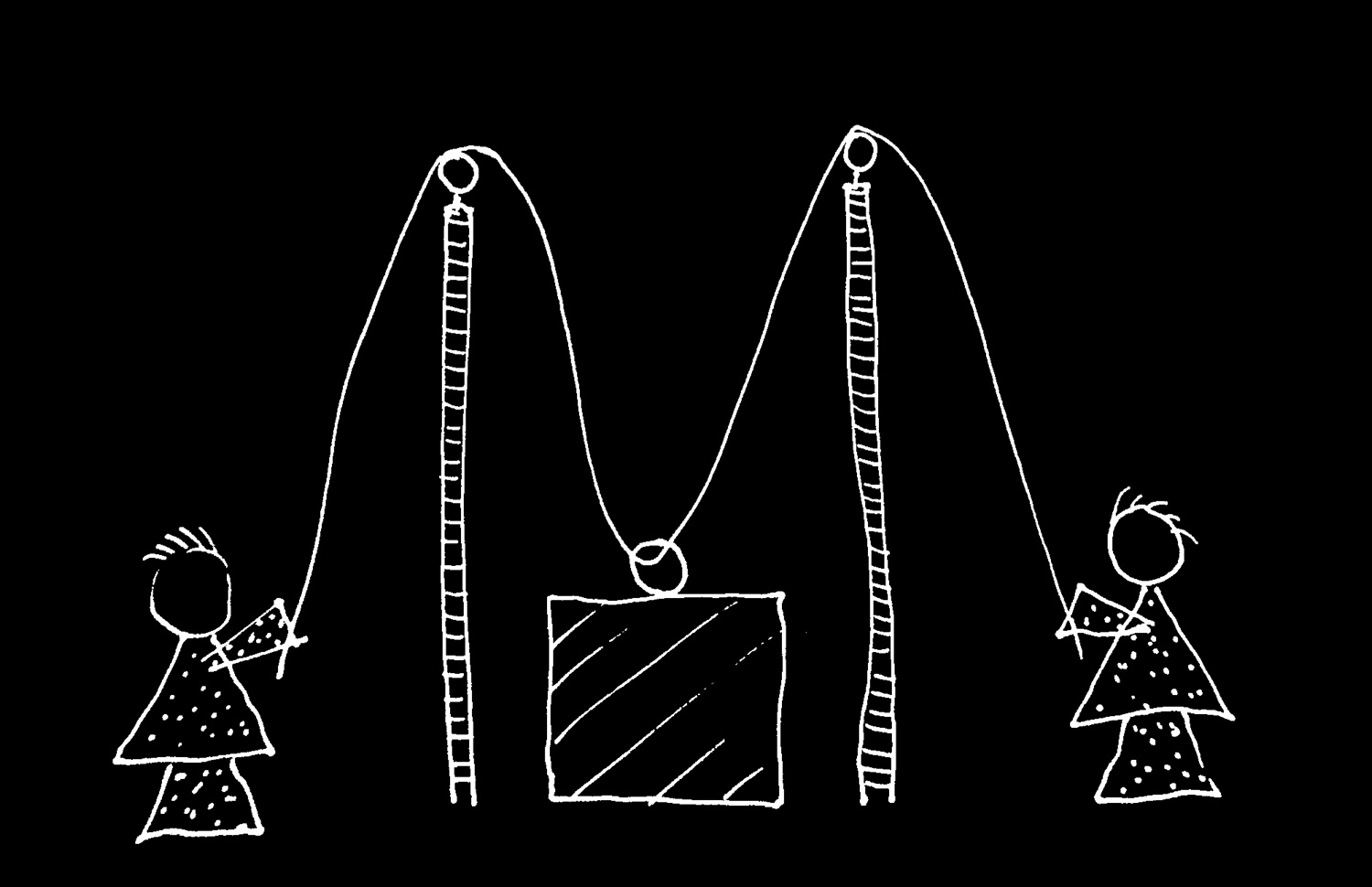

Are Ayesha and Beatrice

acting together?

Is Ayesha and Beatrice’s

lifting the block together

a joint action?

We each intend that we, you and I, cycle to school together.

‘[H]ow can an individual refer to a joint activity without the jointness [...] already being in place?’ (Schweikard and Schmid, 2013)

terminology:

shared agency

joint action

‘collective’ action / agency

---

acting together