Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Question

What distinguishes genuine joint actions from parallel but merely individual actions?

Diagnosis

Too reflective!

Grounded merely on intuitive contrasts!

Thing to Be Explained

Candidate Explanation

Dimming of a star.

Conjecture about a planet.

Object-tracking abilities in infants.

Conjecture about innate knowledge.

Abilities to act together.

Conjecture about shared intention.

walking together

singing a duet together

painting a house together

having a conversation together

making dinner together

building a hut together

planting a garden together

? Walking together in the Tarantino sense ? [non-coercion]

? The strangers blocking the aisle ? [awareness]

? Beatrice & Baldric ? [cooperation]

? Noncommittal walking together ? [commitment]

| Bratman | Simple View Revised | |

| Is coercion compatible with joint action? | yes | yes |

| Does participating in joint action entail being aware that you are doing so? | yes | [ish] |

Are all joint actions cooperative actions? | no | yes |

| Are contralateral commitments necessary for joint action? | no | no |

Examples and contrast cases

are just not enough

to ground a theory of joint action.

Searle vs Bratman on Cooperation

‘One can have a goal in the knowledge that others also have the same goal,

and one can have beliefs and even mutual beliefs about the goal that is shared by the members of a group,

without there being necessarily any cooperation among the members or any intention to cooperate’

Searle, 1990 p. 95

What is shared intention?

Functional characterisation:

shared intention serves to (a) coordinate activities,

(b) coordinate planning, and

(c) structure bargaining

Constraint:

Inferential integration... and normative integration (e.g. agglomeration)

Substantial account:

We have a shared intention that we J if

‘1. (a) I intend that we J and (b) you intend that we J

‘2. I intend that we J in accordance with and because of la, lb, and meshing subplans of la and lb; you intend [likewise] …

‘3. 1 and 2 are common knowledge between us’

(Bratman 1993: View 4)

1. ‘The notion of a we-intention [shared intention]

... implies the notion of cooperation’

Searle (1990, p. 95)

2. Meeting Bratman’s proposed sufficient conditions for shared intention does not imply that youractions will be cooperative.

Therefore:

3. Bratman’s conditions are not in fact sufficient.

‘This involves a bit of linguistic legislation’

Bratman, 2015 p. 38

| Bratman | Simple View Revised | |

| Is coercion compatible with joint action? | yes | yes |

| Does participating in joint action entail being aware that you are doing so? | yes | [ish] |

Are all joint actions cooperative actions? | no | yes |

| Are contralateral commitments necessary for joint action? | no | no |

Examples and contrast cases

are just not enough

to ground a theory of joint action.

Examples and contrast cases

are just not enough

to ground a theory of joint action.

How can we go about constructing

a theory of phenomena

associated with acting together?

How to go about constructing a theory of phenomena associated with acting together?

Step 1: identify features associated with things commonly taken to be paradigm joint actions in non mechanistic terms, e.g.

- collective goals

- coordination

- cooperation

- contralateral commitments

- ...

Step 2: generate how questions.

Step 3: answer the how questions.

Step 4: determine implications for philosophical approaches to joint action.

Collective Goals

goal != intention

What is the relation between a purposive action and the outcome or outcomes to which it is directed?

goal != intention

The tiny drops fell from the bottle.

- distributive

The tiny drops soaked Zach’s trousers.

- collective

Their thoughtless actions soaked Zach’s trousers. [causal]

- ambiguous

The goal of their actions was to fill Zach’s glass. [teleological]

- also ambiguous

Joint action:

An event with two or more agents where the actions have a collective goal.

[Too broad!]

Better approach:

In virtue of what could two or more agents’ actions have a collective goal?

objection

Is there a collective interpretation

of ‘The goal of their actions was to fill Zach’s glass’?

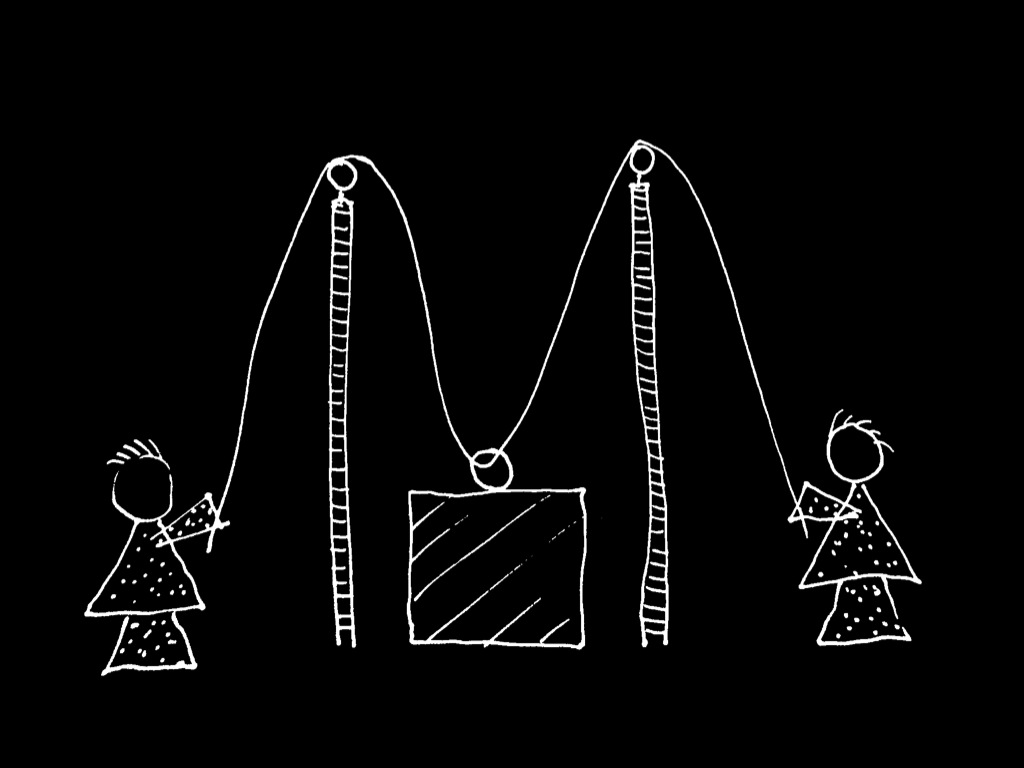

If

there is a single outcome, G, such that

(a) Our actions are coordinated; and

(b) coordination of this type would normally increase the probability that G occurs.

then

there is an outcome to which our actions are directed where this is not, or not only, a matter of each action being directed to that outcome,

i.e.

our actions have a collective goal.

A collective goal (df):

an outcome to which two or more agents’ actions are directed

where

this is not, or not only,

a matter of each action being directed to that outcome.

What distinguishes genuine joint actions from parallel but merely individual actions?

In virtue of what could two or more agents’ actions have a collective goal?

Separate projects:

Characterise the thing to be explained!

Identify the thing(s) which explain(s) it!

conclusion

- Examples and contrast cases

are just not enough

to ground a theory of joint action. - A better approach: identify features independently of characterising mechanisms.

- Collective goals are a feature of some or all joint actions.

How to ground a theory of joint action?

Step 1: identify features ...

- collective goals

- coordination

- cooperation

- contralateral commitments

- experience

Step 2: ... which generate how questions.