Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

On accounts like Bratman’s or Gilbert’s, ‘it makes some sense to say that the result is a kind of shared action: the individual people are, after all, acting intentionally throughout.

However, in a deeper sense, the activity is not shared: the group itself is not engaged in action whose aim the group finds worthwhile, and so the actions at issue here are merely those of individuals.

Thus, these accounts ... fail to make sense of a ... part of the landscape of social phenomena’

Helm (2008, pp. 20-1)

How?

aggregate subject

Gilbert: All joint commitments are commitments to emulate, as far as possible, a single body which does something (2013, p. 64).

In manifesting any collective phenomenon, we can truly say ‘We have created a third thing, and each of us is one of the parts’

Gilbert (2013, p. 269).

Are There Joint Commitments?

Gilbert: joint commitment is irreducible to personal commitment

Compare blocking.

Are there joint commitments?

For us to collectively lift the table

For Ahura to be personally committed

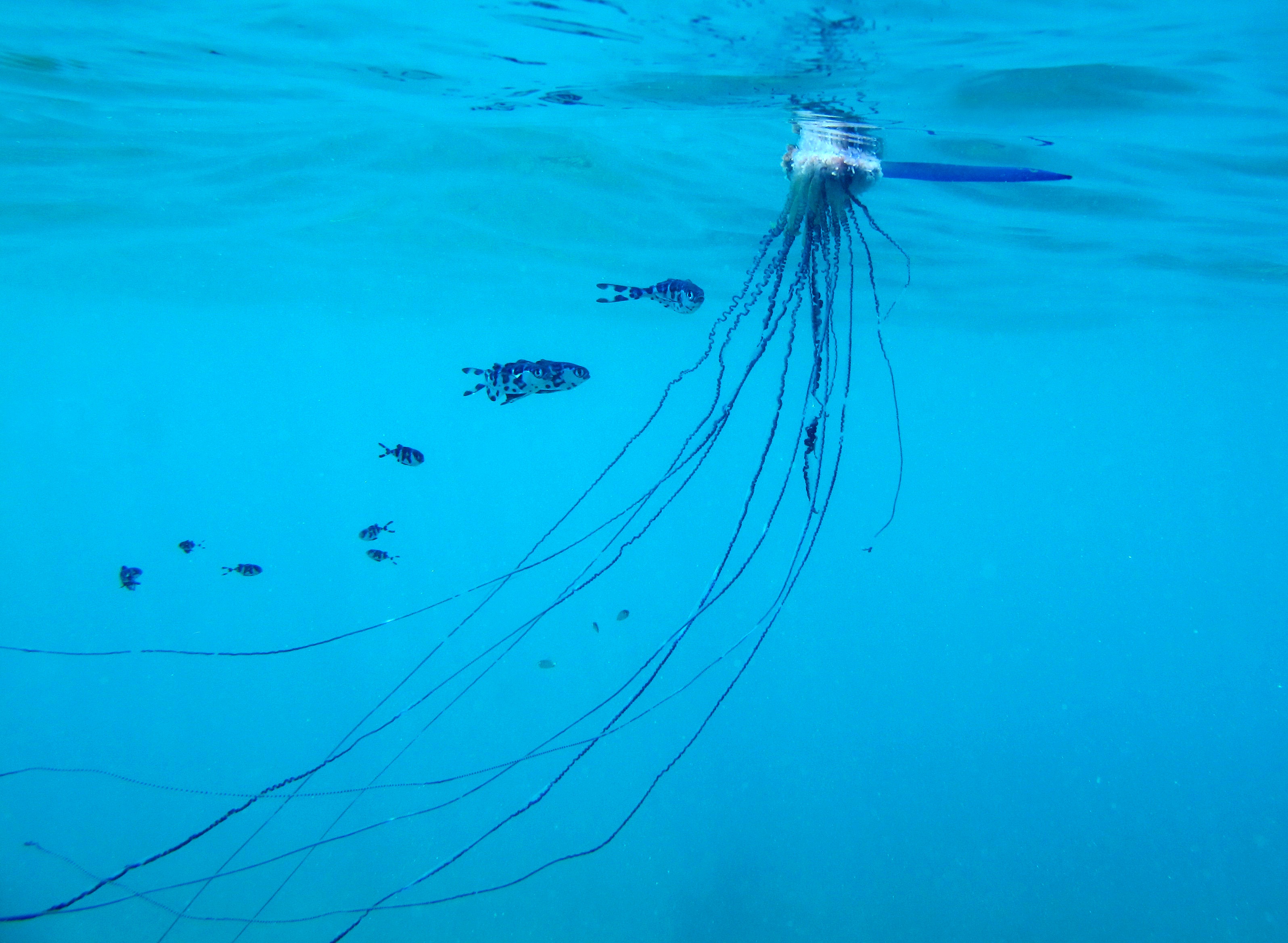

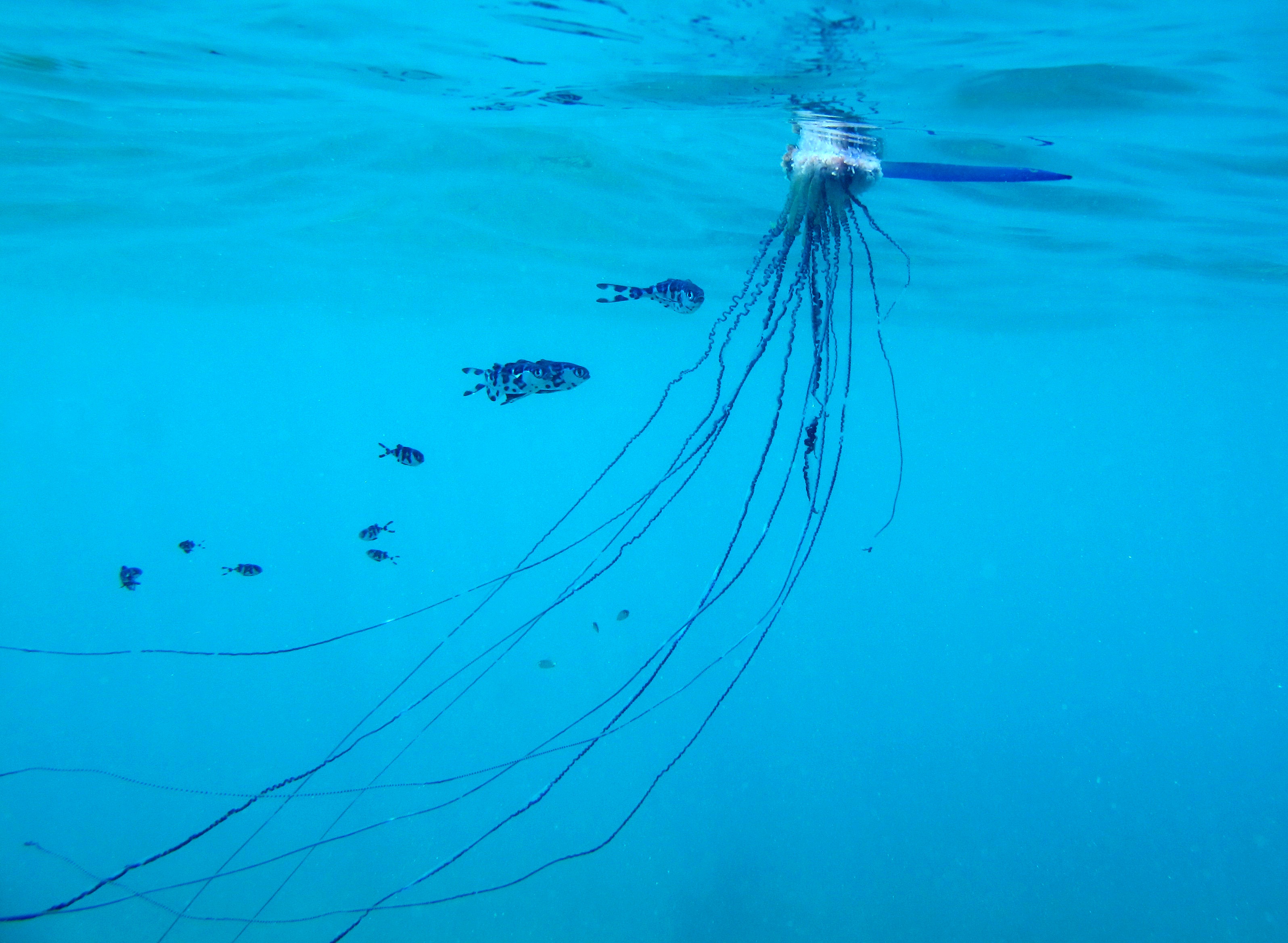

Are there collective infections?

- collective addictions?

- collective deaths?

- collective feelings?

- ...

‘what is needed, to put it abstractly, is expressions of readiness on everyone’s part to be jointly committed [...]. Common knowledge of these expressions completes the picture.’

Gilbert (2013, p. 253)

‘this is pretty much the whole story’

Gilbert (2013, p. 48)

Not: I’m ready if you are.

what is needed is expressions on everyone’s part of readiness to lift the table.

what is needed is an expression of readiness on Ahura’s part to be committed.

Are there joint commitments?

‘Jessica says, “Shall we meet at six?” and Joe says, “Sure.”’

Joint or merely symmetric contralateral commitments?

Maybe.

Gilbert hasn’t shown that there are.

1. A joint commitment is a commitment we have collectively.

(So joint commitment is a commitment.)

2. Gilbert shows joint commitments exist.

3. Joint commitments ground contralateral commitments.

Joint and Contralateral Commitment: Objection to Gilbert on Shared Intention

For us to have

a shared intention that we φ

is for us to be jointly committed

to emulate a single body

which

intends to φ

‘When people regard themselves as collectively intending to do something, they appear to understand that, by virtue of the collective intention, and that alone, each party has the standing to demand explanations of nonconformity [...]. A joint commitment account of collective intention respects this fact. ’

Gilbert (2013, pp. 88–9)

1. Shared intentions are associated with contralateral commitments.

2. This is a fact which stands in need of explanation.

3. That shared intentions are joint commitments (to emulate a single body which intends to ...) explains this fact.

Gilbert: joint commitment

‘a commitment

by two or more people

of the same two or more people.’

joint commitment is ‘the collective analogue of a personal commitment’

Gilbert (2013, p. 85)

Contrast contralateral commitment (by me, of me, to you)

joint vs contralateral

- compare -

orgy vs reciprocal

we teach ourselves to code vs we teach each other to code

Observation: shared intentions are associated with contralateral commitments.

Question: What is their source?

- individual intentions? no!

- conditional intentions? no!

- joint commitments? no!

‘just as—in the case of a personal commitment—you are in a position to berate yourself for failing to do what you committed yourself to do, all of those who are parties with you to a given *joint* commitment are in a position to berate you for failing to act according to that joint commitment’ (p. 401).

Gilbert (2013, p. 401)

Collective entails individual?

- blocking: no

- state of disarray: no

- blame: no?

- commitment: no

For us to have

a shared intention that we φ

is for us to be jointly committed

to emulate a single body

which

intends to φ

‘When people regard themselves as collectively intending to do something, they appear to understand that, by virtue of the collective intention, and that alone, each party has the standing to demand explanations of nonconformity [...]. A joint commitment account of collective intention respects this fact.’

Gilbert (2013, pp. 88–9)

1. Shared intentions are associated with contralateral commitments.

2. This is a fact which stands in need of explanation.

3. That shared intentions are joint commitments (to emulate a single body which intends to ...) explains this fact.

1. A joint commitment is a commitment we have collectively.

(So joint commitment is a commitment.)

2. Gilbert shows joint commitments exist.

3. Joint commitments ground contralateral commitments.

4. Shared intentions are joint commitments to emulate a single body that intends ...

conclusion

Gilbert: joint commitment

‘a commitment

by two or more people

of the same two or more people.’

Questions

Are joint commitments simply commitments we have collectively?

Has Gilbert shown that joint commitments exist? (Or can you?)

Do joint commitments ground contralateral commitments?

Are shared intentions joint commitments to emulate a single body which intends something?