Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

The Simple View

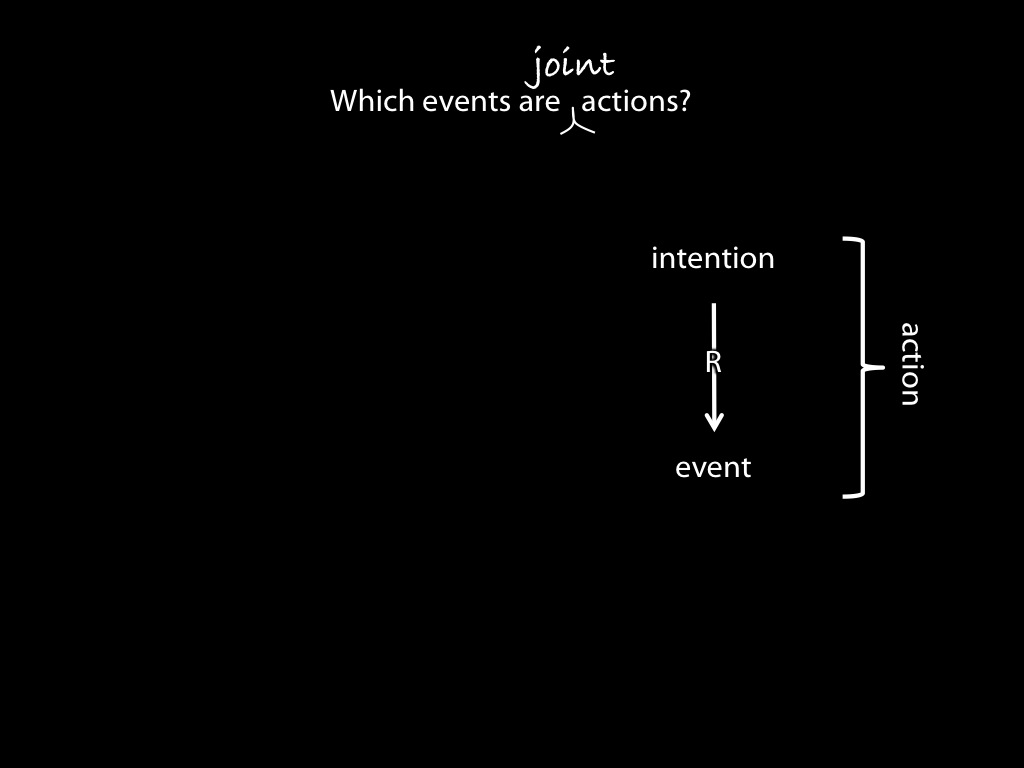

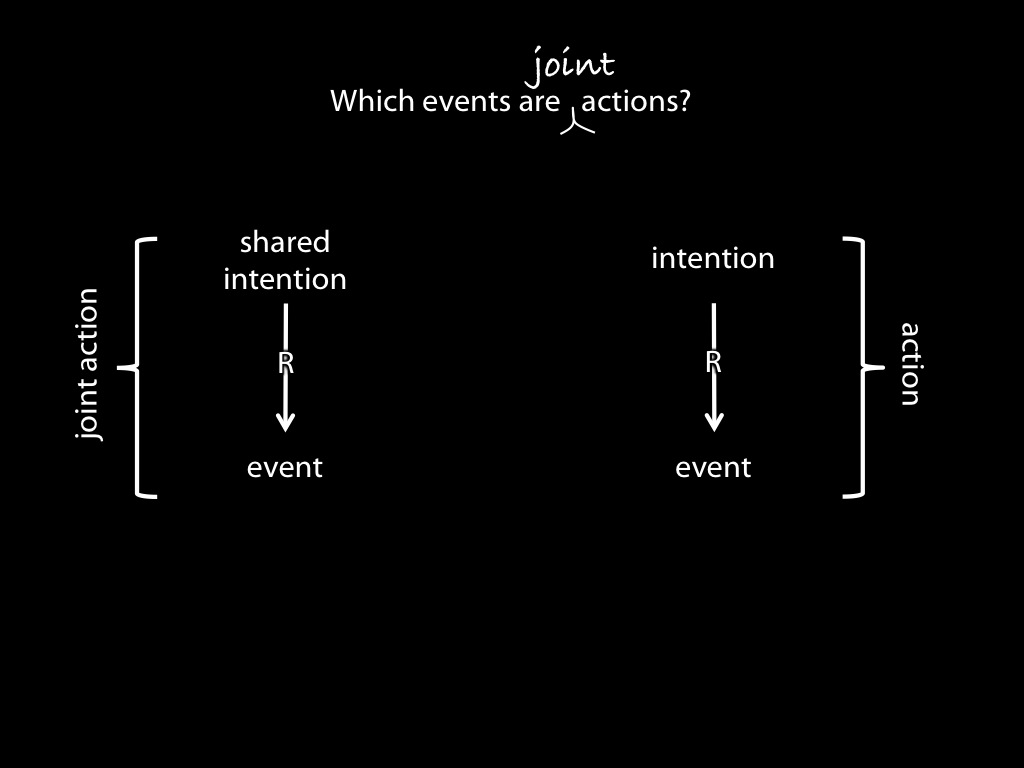

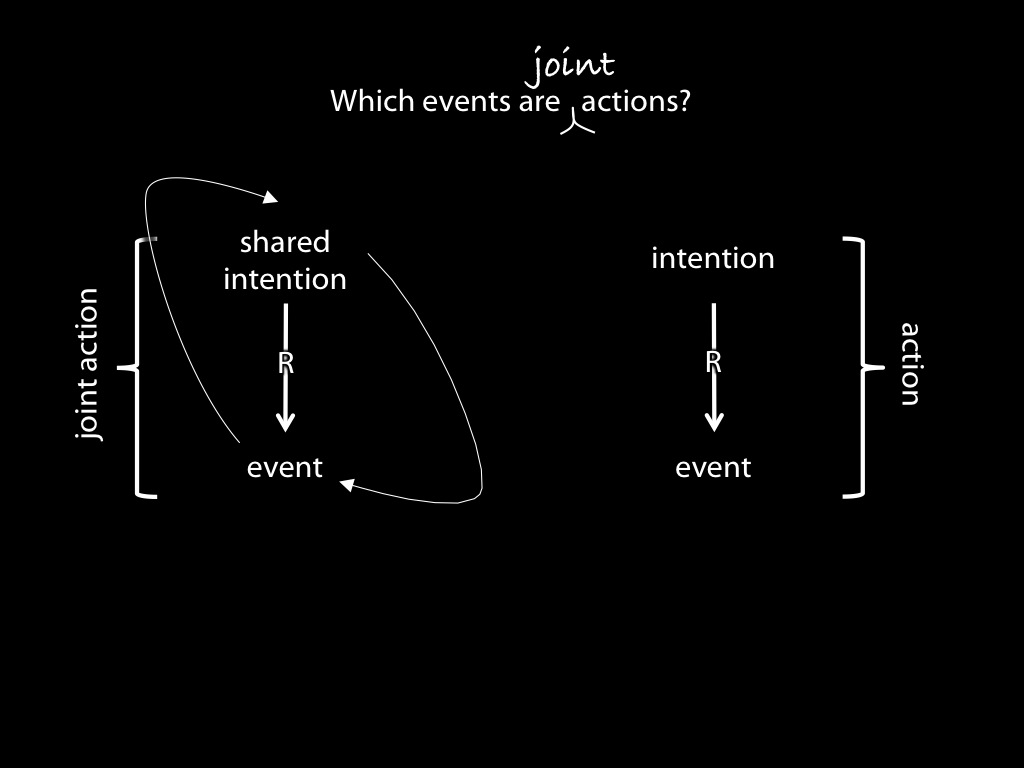

Two or more agents perform an intentional joint action

exactly when there is an act-type, φ, such that

each agent intends that

they, these agents, φ together

and their intentions are appropriately related to their actions.

Bratman’s ‘mafia case’

1. I intend that we, you and I, go to NYC together.

2. You intend that we, you and I, go to NYC together.

3. You intend that we, you and I, go to NYC together by way of you forcing me into the back of my car.

Walking together in the Tarantino sense

1. I intend that we, you and I, walk together.

... by means of my forcing you at gun point.

2. You intend that we, you and I, walk together.

... by means of you forcing me at gun point.

the threat of collapse: trading intuitions

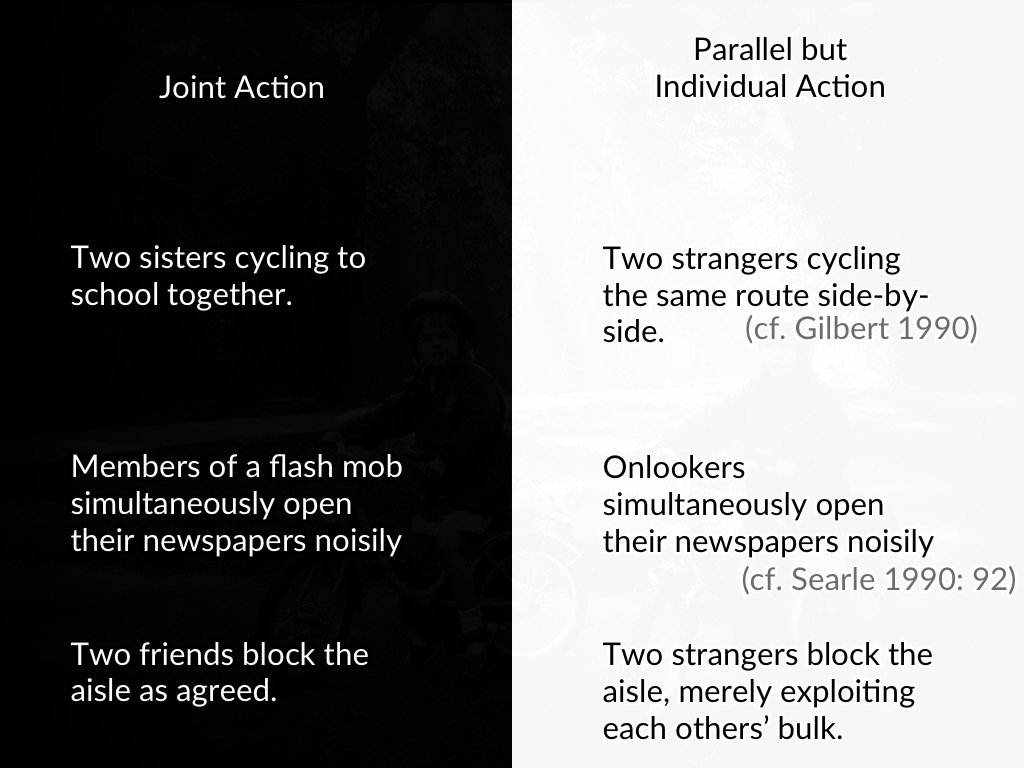

another contrast case: blocking the aisle

1. The sisters perform a joint action; the strangers’ actions are parallel but merely individual.

2. In both cases, the conditions of the Simple View are met.

therefore:

3. The Simple View does not correctly answer the question, What distinguishes genuine joint actions from parallel but merely individual actions?

Is it a genuine counterexample?

Question

What distinguishes genuine joint actions from parallel but merely individual actions?

The Simple View

preview

‘each agent does not just intend that the group perform the […] joint action.

‘Rather, each agent intends as well that the group perform this joint action in accordance with subplans (of the intentions in favor of the joint action) that mesh’

(Bratman 1992: 332)

We have a shared intention that we J if

‘1. (a) I intend that we J and (b) you intend that we J

‘2. I intend that we J in accordance with and because of la, lb, and meshing subplans of la and lb; you intend [likewise] …

‘3. 1 and 2 are common knowledge between us’

(Bratman 1993: View 4)

Shared Intention: A Placeholder

shared intention

‘A first step is to say that what distinguishes’ the sisters cycling together from the strangers cycling side by side is that the sisters share an intention to cycle together ... but the strangers do not.

‘In modest sociality, joint activity is explained by such a shared intention; whereas no such explanation is available for the combined activity’ of those who are acting in parallel but merely individually.

‘This does not, however, get us very far; for we do not yet know what a shared intention is’

Bratman, 2009 p. 152

‘I take a collective action to involve a collective [shared] intention.’

(Gilbert 2006, p. 5)

‘The sine qua non of collaborative action is a joint goal [shared intention] and a joint commitment’

(Tomasello 2008, p. 181)

‘the key property of joint action lies in its internal component [...] in the participants’ having a “collective” or “shared” intention.’

(Alonso 2009, pp. 444-5)

‘Shared intentionality is the foundation upon which joint action is built.’

(Carpenter 2009, p. 381)

?

shared intention

Parallel with individual action ...

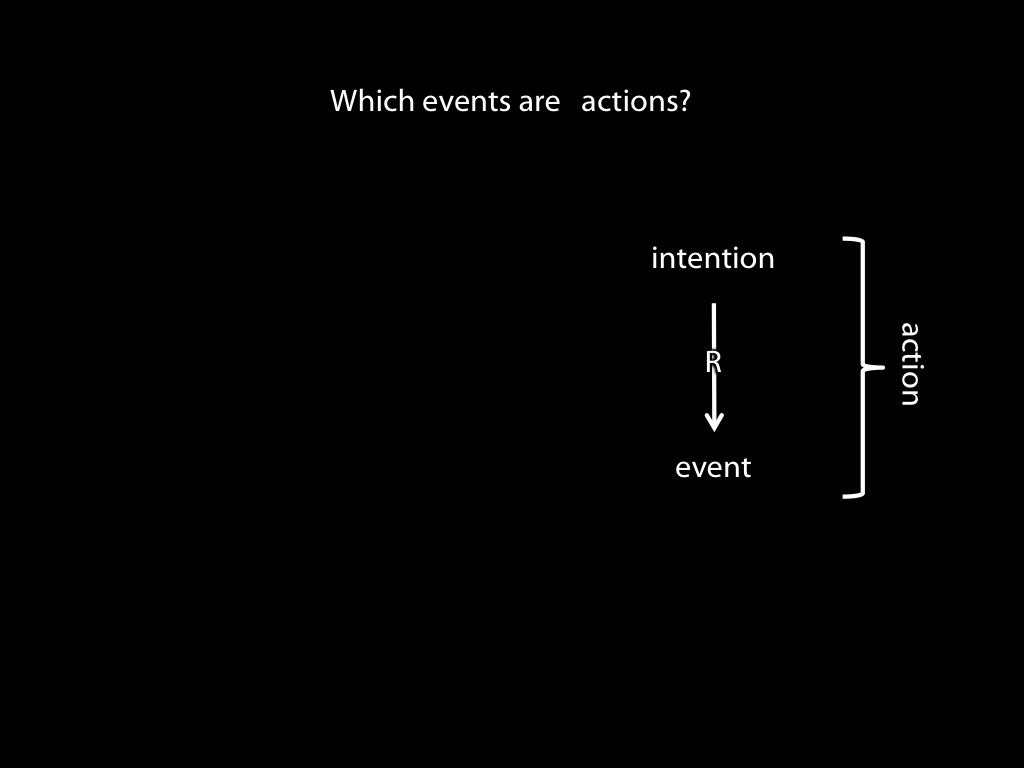

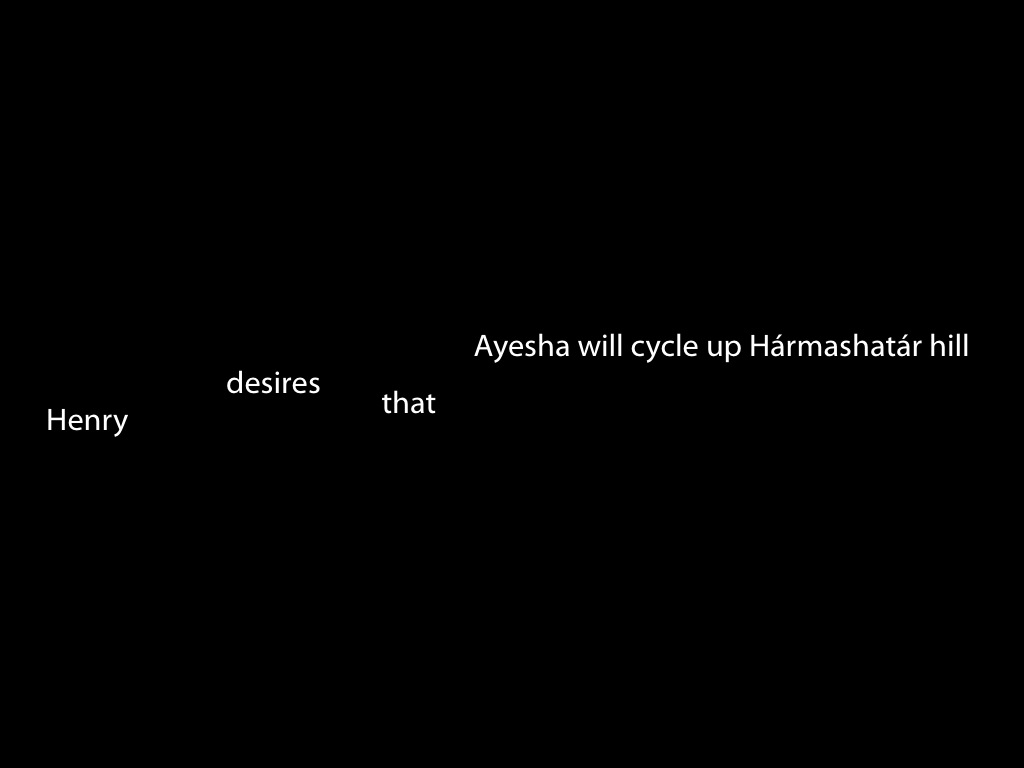

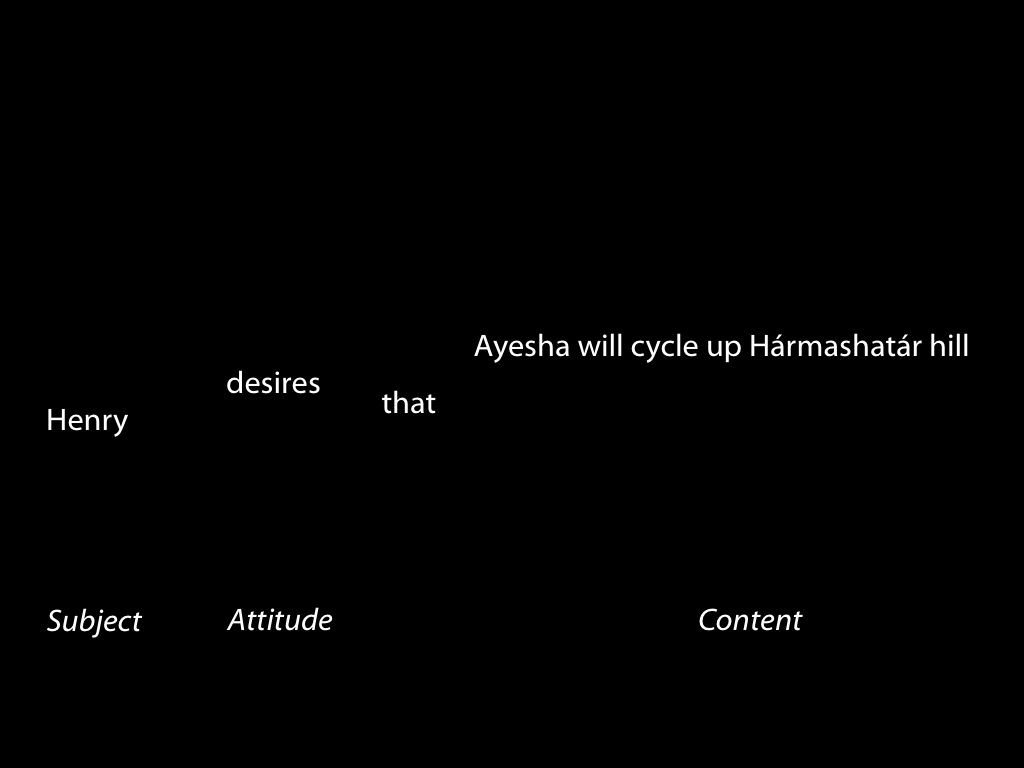

‘What events in the life of a person reveal agency; what are his deeds and his doings in contrast to mere happenings in history; what is the mark that distinguishes his actions?’

Davidson (1971, p. 43)

?

shared intention

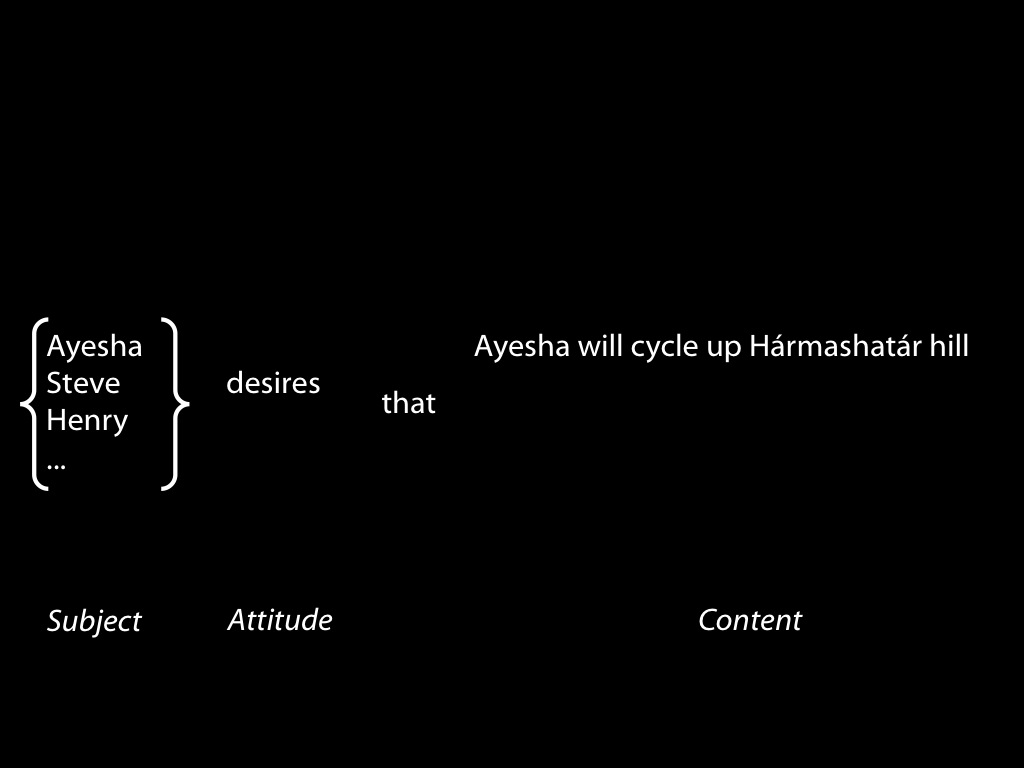

‘shared’ 1 : Ayesha and her best friend have the same haircut

-> the Simple View

‘shared’ 2 : Ayesha and her brother share a mother

-> plural subject account (Schmid, Helm)

e.g. our volume, yours and mine, is approx 130 litres.

cf. our intention, yours and mine, is that we paint the house.

‘shared’ 1 : Ayesha and her best friend share a name

-> the Simple View

‘shared’ 2 : Ayesha and her brother share a mother

-> plural subject account

Can intentions have

plural subjects?

?

shared intention

conclusion

- ‘Blocking the aisle’ provides a counterexample to the Simple View (at last!).

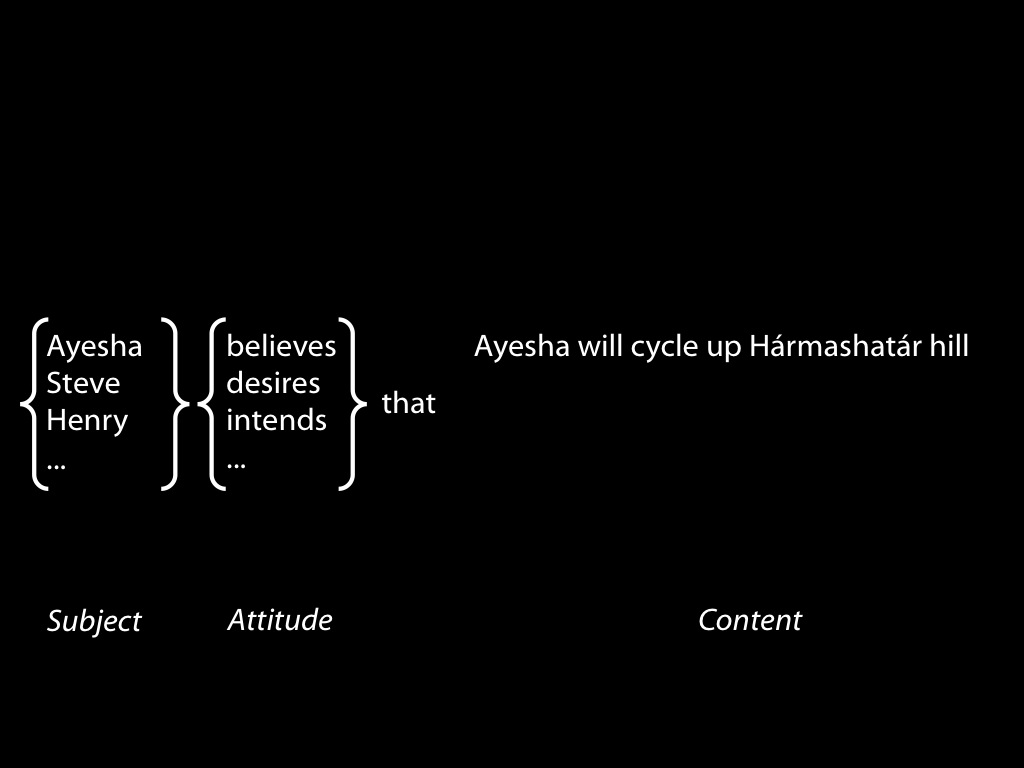

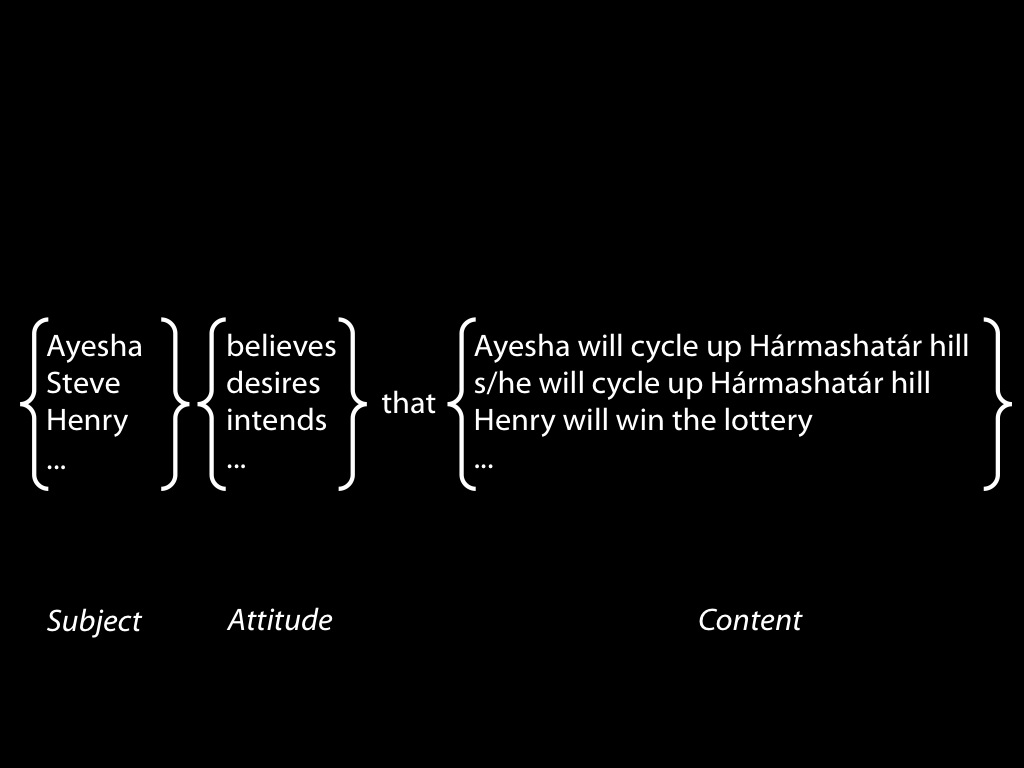

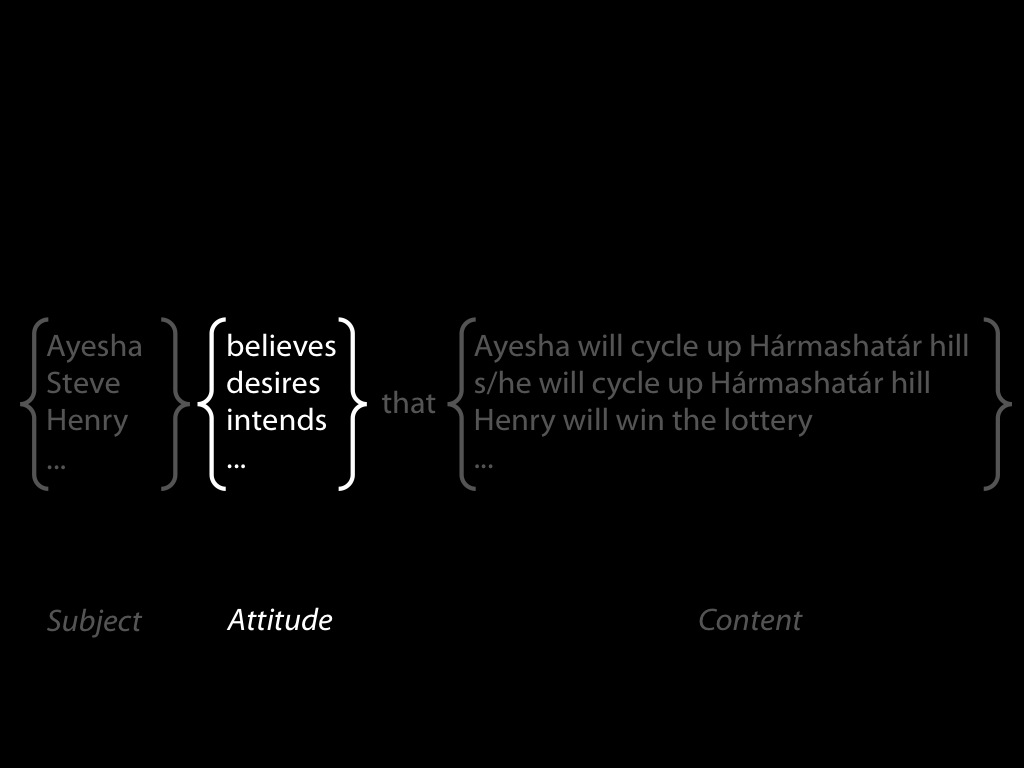

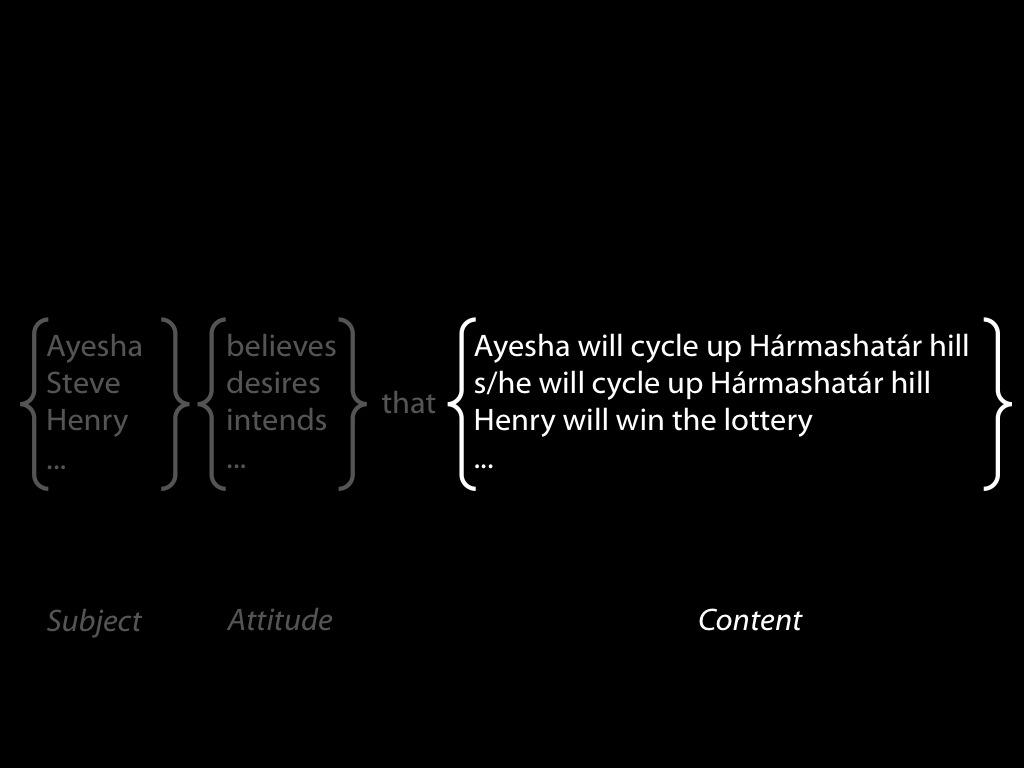

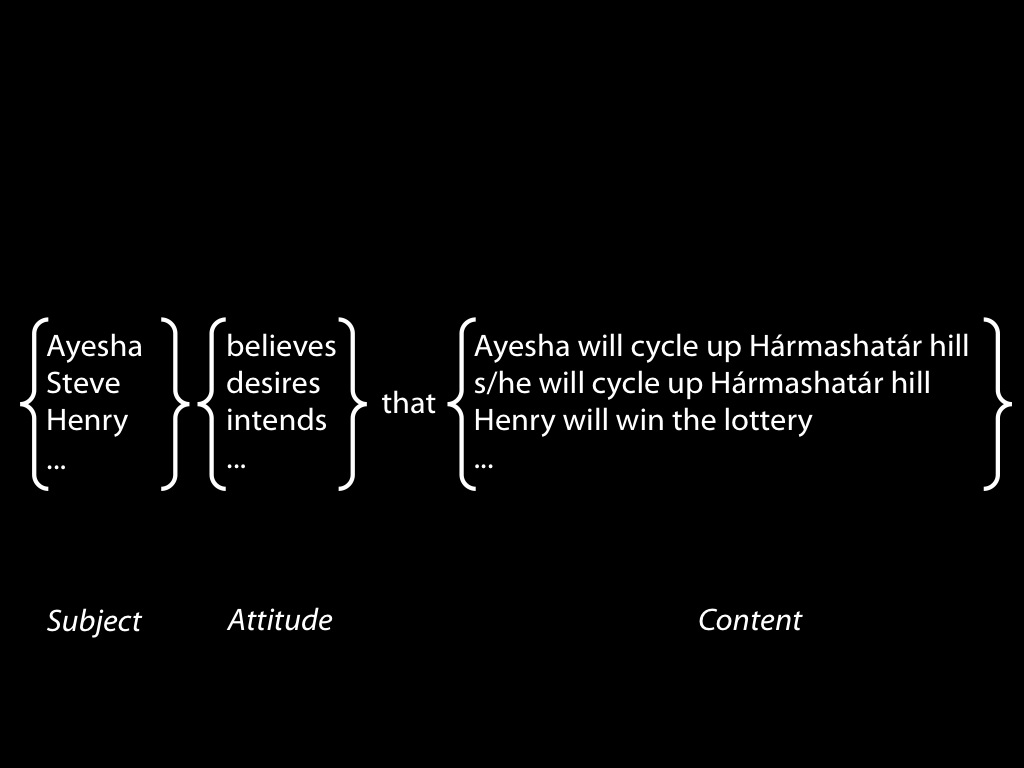

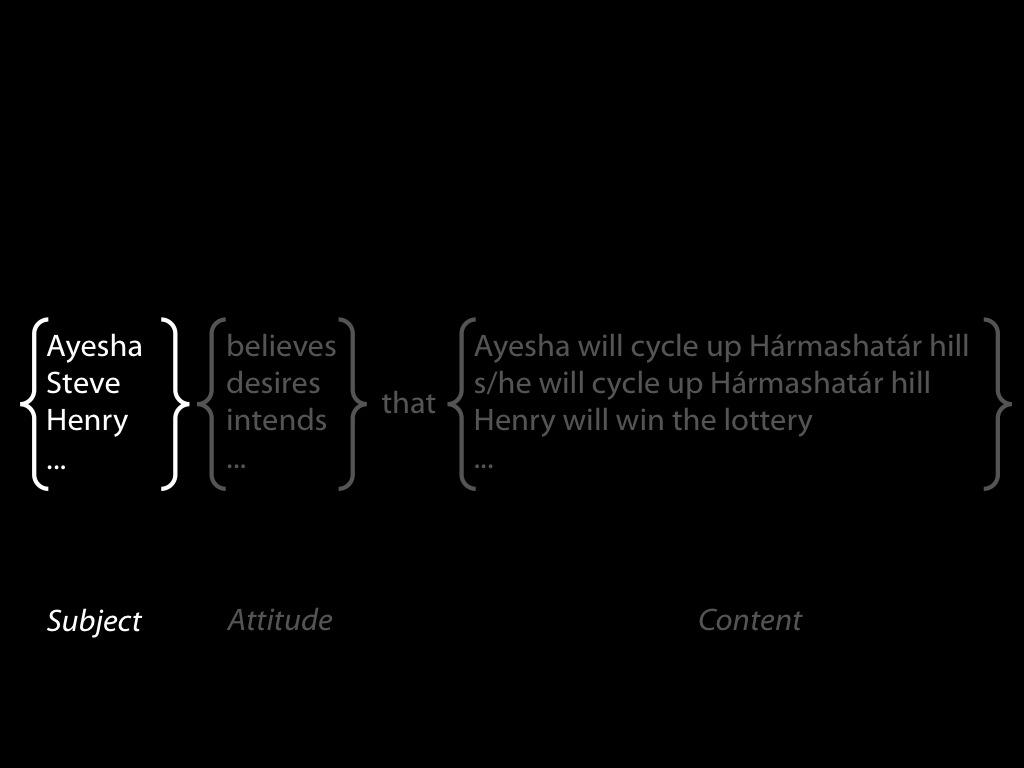

- Three basic features of mental states are: subject, attitude and content.

- An alternative approach involves shared intention.

- We don’t know what shared intentions are:

- ... they can be characterised by invoking plural subjects (more on which later)

- ... but on most accounts they are neither shared nor intentions.